What is the biggest geologic hazard facing the California? We have famously had disasters caused by earthquakes, floods, wildfires, and dam failures. But at least we don't have to worry about a Katrina-style disaster, of losing an entire city to floods brought on by levee failure during a major hurricane. Or do we?

Welcome to the Sacramento Delta. The Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers drain most of the Sierra Nevada and Central Valley, and represent

50% of the available water resources in the state. The Delta is practically unique in the world. Most deltas extend out to the sea, like the Nile or Mississippi, but the Sacramento is far inland. This is a consequence of sea level rise following the end of the last ice age, and the arrangement of structural blocks that compose the Coast Ranges, which forces the vast drainage through a single channel at the Carquinez Straits. The Sacramento and other rivers break up into a series of sloughs and channels that define around 60 "islands". These islands were once rather ephemeral, changing as a result of yearly floods and runoff events. When the agricultural potential of the islands was recognized in the 1800's, they were surrounded and outlined by a series of levees to stop the seasonal flooding. Ultimately an area of 1,150 square miles came under the plow.

The law of unintended consequences was certainly in effect here. The peat-rich soils were originally anaerobic marshes, and buried carbon stayed buried. Once farming began, the groundwater was not constantly being recharged, the drier soils began to oxidize, and the land began to subside at a rate of an inch or two every year. Today the majority of the islands are below sea level, in many cases by as much as 10 to 25 feet. The levees prevent flooding by holding back the rivers and sloughs on a year-round basis. It is quite interesting to drive across the delta, and climb

uphill in order to cross the rivers and channels!

The construction of the levees had another effect that is essentially a positive, but is also a problem. The delta is subject to tidal changes, and saltwater intrudes into the delta during high tides and droughts. Prior to levee construction, the saltwater intruded many miles further into the delta, but in recent decades the intrusion has been far less (this is also an effect of water releases from dams far upstream).

Which leads us to California's huge vulnerability: what happens if the 1800's-vintage levees fail? We have a pretty good idea because it happens on a much too regular basis, more than 100 times since 1890. Major flood events like the 1997 disaster caused levee failures in several places. Some failures have been caused by trivial things like muskrat burrowings. Singular events such as these have flooded thousands of acres. But what would happen if dozens of the islands were flooded all at once? Unthinkable? Unfortunately a very real possibility. It's all about earthquakes.

The saturated earthen levees are subject to

liquefaction, where a loss of cohesion of the soil results from the breakdown of the surface tension of the water that was holding the grains together. Think of it this way. A sand castle holds its shape in damp sand, but loses it if too much water is added. If you stomp on wet sand at the beach, it will liquefy, and you will sink a few inches. The same thing can happen on a large scale with a levee, and thus earthquakes stand as one of the most greatest threats to the integrity of the levee system. And the system has not been truly tested: many of the levees hadn't yet been finished in 1906, and the 1989 Loma Prieta quake (magnitude 6.9) was too distant from the delta to have much of an effect. But a number of active faults pass through or near to the delta, and it won't require a "BIG ONE" to do the damage. A 6.0-6.5 near by on one of these faults will be more than enough.

If widespread levee failure takes place, dozens of islands will be flooded with saltwater, and the thousands of acres of prime agricultural lands will be lost. To be sure, thousands of people live on these tracts, and they will be homeless, perhaps permanently (is it really worth it to reclaim an island that is 25 feet deep in salt water?). But this isn't the biggest problem. It's that fact that 23 million people, most of the population of the state, are depending on delta water for their domestic and agricultural use.

The California Water Project and other systems pump water out of the delta for use by cities and farms off to the south. In the event of a worst-case scenario earthquake, the pumps will be fouled by salt water for months or even years. The state's single largest source of fresh water will be gone. It's a huge problem that until recently was not receiving attention, but apparently that has changed, and the

legislature and governor are catching up to the pleas of the water managers about the huge vulnerability of our water systems.

There are great many other issues with the use of water in California, of which the problems of the delta are only a part: a

rather extensive review can be found here. Droughts, climate change, ecosystem deterioration, and water waste are all serious problems that have to be dealt with pretty much immediately. But preventing a

Katrina-style levee failure has to be near the top of the list. It could literally happen tomorrow...

I snapped today's picture if the Sacramento Delta on a flight out of San Francisco in 2006.

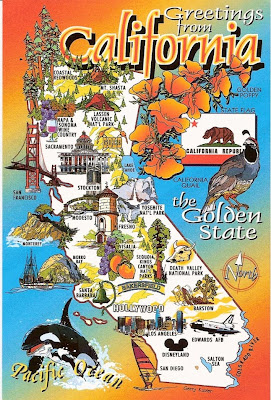

I wrote a post a few days ago about the "Other California", describing a section of the prairies that surround California's Central Valley, a much diminished and much ignored part of an extraordinary state. The title I gave the post stuck with me as I drove across about half the state on my way to a family Thanksgiving celebration, and I had the germ of an idea of a future series on Geotripper, a geologic tour of the parts of the state that most people never see. It occurred to me that if I am going to write about the "Other California", I need to define what the "Other California" is not, hence today's odd title.

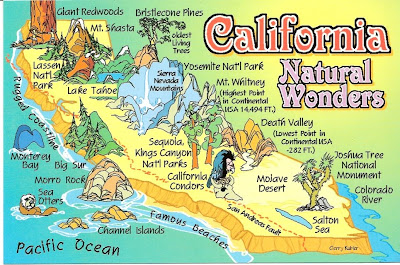

I wrote a post a few days ago about the "Other California", describing a section of the prairies that surround California's Central Valley, a much diminished and much ignored part of an extraordinary state. The title I gave the post stuck with me as I drove across about half the state on my way to a family Thanksgiving celebration, and I had the germ of an idea of a future series on Geotripper, a geologic tour of the parts of the state that most people never see. It occurred to me that if I am going to write about the "Other California", I need to define what the "Other California" is not, hence today's odd title. I like the second card even more: the Natural Wonders of the State. The same national parks, plus Lake Tahoe, the Colorado River (so big and wide that it looks like California is probably already falling into the sea), the Mojave Desert, Bristlecone Pines, California Condors, Sea Otters, Mt. Shasta, and Morro Rock. Best of all, a red dotted line representing the San Andreas fault winds its crooked way across the state. I don't necessarily expect perfection in postcard maps, but this one takes the cake!

I like the second card even more: the Natural Wonders of the State. The same national parks, plus Lake Tahoe, the Colorado River (so big and wide that it looks like California is probably already falling into the sea), the Mojave Desert, Bristlecone Pines, California Condors, Sea Otters, Mt. Shasta, and Morro Rock. Best of all, a red dotted line representing the San Andreas fault winds its crooked way across the state. I don't necessarily expect perfection in postcard maps, but this one takes the cake!