Introduction: Glacier Point at Yosemite National Park (from April 22, 2014)

What is the most incredible place you have ever stood? That thought occurred to me this last weekend when I got up to Glacier and Washburn Points in Yosemite National Park. For those who are less familiar with the park, Glacier and Washburn Points are on the rim of Yosemite Valley, not on the valley floor. As such, they give a bird's-eye view of one of the most incredible pieces of land in the world, and though a million or more people may stop there during their visit to Yosemite, I'll bet the majority of park visitors don't venture up that way. It's something like 20 winding miles outside of tourist central on the valley floor, and perhaps hard to squeeze in when trying to rush through the park in the limited moments afforded by a vacation.

Is the high point on the rim of Yosemite Valley the greatest spot I've ever stood? I'm not sure yet! This is the opening salvo of a new series called the Ten Most Incredible Places, and I'm going to decide number one somewhere along the way before I finish. I'd also like you to consider what your own most incredible places are. I'd love to have you share them, perhaps in your own blog if you have one, or share them in the comments here. I'd be glad to post a few of your wonderful pictures as I consider my list. Be sure to include some reasons why a particular place stands out, whether geological, biological, spiritual, or personal.

Number 10: The Alaka'i Swamp, Kauai, Hawai'i (from April 22, 2014)

My list is not in a precise order. Listing a favorite among these is tantamount to selecting which of my children I love the most. I am saving my most precious for number one, but aside from that, these are all equally incredible. I've not made any rules about these sites; some required long hikes, others I drove to. Some are all about the geology, some are about other things.

So what is this place today? It's cold, it's wet, it's made up mostly of waist-deep mud, and basically the last kind of environment that one would ever thinks exists in the state of Hawaii. Where are the palms and sandy beaches?

They are about 4,000 feet and a world away.

On the island of Kaua'i, some of the preconceptions of Hawai'i fall by the wayside. There are numerous examples of iconic coral sand beaches and offshore reefs. But there is also a deep gorge that has been called the Grand Canyon of the Pacific (Waimea Canyon), which almost made my top-ten list. But there is a region on the island that is practically unique to the world: a high altitude swamp and rainforest complex that is one of the wettest places on the planet. It's called the Alaka'i Swamp, and it is part of the Waialeale Plateau, a place where the average yearly rainfall is close to 40 feet. In 1982, 683 inches of rain fell. That's 57 feet!

|

| A friendly 'Elepaio in the Alaka'i Swamp |

The native birds of the Hawaiian Islands provide a laboratory for the study of evolution no less significant than Darwin's Galapagos Islands. But the birds are under siege. Numerous invasive bird species came with the humans, along with wild pigs, mongooses, and malaria-bearing mosquitoes. Few birds seen by tourists are actually natives. The natives survive mostly at elevations above 3,000 feet where the mosquitoes can't thrive. Of the original 71 known species of birds on the Hawaiian Islands, 24 are extinct, and 32 are severely endangered. They've lost out to competition, habitat loss, disease, and predation (by the mongooses, which are as common as squirrels in the urban parks on the islands). Mongooses were never introduced on Kaua'i, so the higher parts of the island are the best places to see the rare natives like the 'Elepaio in the picture above (other birds are much rarer, but this was the only one I saw on my hike).

In 2009 I had the privilege of hiking the 5 mile trail (one-way) to Kilohana Overlook. It was one of the great adventures of my life. The trail began at the Na Pali Overlook and parking lot. The first mile was on a usually closed paved road to a second overlook. After that it was up and down on some potentially muddy trails, but we lucked out and didn't get rain that day. Eventually we were walking through the deep 'Ohi'a forest.

'Ohi'a trees are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, and are one of the most adaptable trees on the planet, capable of growing on barren lava flows in near-desert conditions at sea level to cold, almost alpine conditions at 8,200 feet. The trees have beautiful red flowers that look like small red fireworks exploding from the branches.

The flowers are called "Lehua", and they figure prominently in Hawaiian mythology. The tree was a handsome young man, 'Ohi'a, who spurned the attentions of Pele, the volcano goddess. He was in love with Lehua instead. In a fit of anger, Pele turned the young man into a tree, but later repented and adorned the trees with his beautiful lover, the Lehua.

When we climbed onto the high plateau, it got...weird. Just low brush and ferns, with mud everywhere. We were fortunate the rain wasn't pouring on us by this point.

In the distance on this extraordinarily clear and sunny day, we could see the slopes leading to the high point of the island at Mt. Waialeale. Part of me wanted to leave the trail and explore the strange wilderness off to the south, but I knew I would be up to my knees or worse after the first few steps. We kept to the trail!

Mud was now everywhere, enough to creep us out a little. This is an environment almost entirely alien to humans. We were now getting close to the end of the trail at the Kilohana Overlook. It's not a good idea to have the view from the Kilohana as an ultimate goal for hiking the trail. Most of the time, the overlook is bathed in clouds. I hiked to the edge and looked into the abyss below.

It was clear! We could see deep into the canyon of Waihina River gorge. I don't think I've ever seen more inaccessible slopes. Impenetrable slopes choked with rainforest vegetation, and not even a hint of a trail. Leaning over the edge, it was hard to tell where the soil ended and the vegetation began.

Down in the distance was the gorgeous bay of Hanalei, 4,000 feet below us. We were at the top of the Wainiha Pali (cliff) in one of the prettiest places I had ever seen.

The skies were fickle, though. Hardly ten minutes passed by and the clouds closed in for good. Some of our party arrived a few moments later and never saw a thing. It was okay though. The overlook was icing on the cake for the strange beauty of a hike through one of the strangest worlds I had ever seen.

Number 9: Frame Arch and the Delicate Arch Trail, Arches National Park, Utah (from April 24, 2014)

Folks will perhaps not be surprised to see that I selected the picture above for my number 9; it's the cover photo from my Geotripper Images website where I've posted a lot of my geological pictures for use in educational/academic projects. It is a view of the La Sal Mountains through Frame Arch at the end of the Delicate Arch trail in Arches National Park.

In the years before PowerPoint, I started all of my geology classes with a set of slides (this was an ancient technology that involved "carousel trays", "slide projectors", and "film") to introduce the students to the world as it is revealed by geological processes. The first picture was always this stretch of trail just short of Delicate Arch. I chose it because it symbolized so much about the wonders revealed in the incredible history of our planet.

The trail is cut into a formation called the Entrada Sandstone, a layer composed mostly of windblown sandstone as well is silt and mud in some areas. It once was a system of sand dunes near a coastal delta and estuary during the Jurassic Period around 140-180 million years ago. The trail surface is a natural separation along the surface on one of the dunes, so by walking on this trail we are striding on the same surface that dinosaurs, ancient mammals, and arthropods walked on many millions of years ago. We know that these rocks were buried deeply by thousands of feet of overlying rock, but they were pushed upwards by vast salt domes rising from older formations below. The doming effect split the rocks into linear fins, and the arches developed from weathering and erosion at the base of fins.

At one viewpoint an observer can appreciate the variety of depositional environments that led to the formation of the colorful Entrada rocks, the vast amount of time that the rocks lay buried in the crust, the immensity of earth movements that brought the rocks back to the surface, and the intensity of erosional processes that shaped the rocks into what they are today. And one can walk on a surface that may very well have been a trackway for a dinosaur many eons ago.

But (like they say in late-night television ads), there's more! Although many people use Frame Arch to frame Delicate Arch, I chose to emphasize the La Sal Mountains instead (the top photo). The La Sals represent the role of magmas in earth processes. The mountains are composed of intrusive rock that reached close to the Earth's surface about 25 to 28 million years ago. Some may even have erupted out in volcanic eruptions, but the rest of the rock formed into mushroom shaped plutons called laccoliths. The dioritic rock proved more resistant to erosion than the surrounding shale and sandstone, so the peaks rise 6,000 to 7,000 feet above the plateau surface. The highest peaks in the La Sals reach nearly 13,000 feet above sea level.

It's a scenic, even iconic spot for photographers and park visitors, but what makes this one spot special to me? It's the unique experience of each visit. It's been my privilege to visit this spot perhaps a dozen times in the last 30 years and every time it has been an awe-inspiring journey. We usually head up the 1.5 mile trail in the late afternoon in order to catch the sunset on Delicate Arch. Quite often there is a raucous crowd, and some moron always feels a need to go stand under the arch for an inordinate period of time, prompting shouted complaints from the large group of photographers on the ridge top. Frame Arch becomes the special spot at that point because there is only myself and a few of my fellow travelers. We don't hear the chaos and mayhem at Delicate Arch, and we can just sit and appreciate the changing colors and deepening shadows.

Once or twice we've been doused with a summer rainstorm, and in one particular year we took shelter under the arch and gloried in the lightning and crashing thunder, and watched as the dry sandstone transformed into a series of waterfalls and white cascades. It was one of the most cherished moments of my life. We assumed that the storm would obscure the sunset, but as quickly as the storm hit, it dispersed and the sunshine broke through to highlight the La Sal Mountains in the far distance.

One more reason that this spot is on my incredible list is because of the ephemeral nature of Delicate Arch itself. It may not last my lifetime. The arch is only a foot and a half thick at one point, and there are valid fears that it could collapse in the natural order of events. Of course, humans may help it along; I've heard of at least one episode in which a man attacked the arch with an axe. Then again, it could last another thousand years. Who knows? In the meantime it is a magic place.

Once before I pass on I would like to see it in the snow.

Number 8: Burgess Shale, British Columbia, Canada (from April 24, 2014)

I've had a rich life, being able to link my favorite activities, traveling and photography, with my career as a geologist and teacher. It means I have been to a lot of places, so determining a list like this leads to a lot of introspection. I've been enjoying reading some of the other entries...I like new ideas of where to go!

I settled on this one particular site because of the emotional impact it had when I reached the goal. It was indeed remote and difficult to get to. It was the Burgess Shale fossil quarry in Yoho National Park in British Columbia, Canada. Besides being one of the most important fossil sites in the world, it involved one of the most beautiful hikes I've ever taken. Just look at the scenery from the edge of the quarry:

Fossilization is a chancy process. Everything has to happen just right, and most of the time organisms are immediately scavenged or quickly decay. Even when things happen just right, it is exceedingly rare for anything besides bone or shell to survive. As a result, the fossil record is highly biased towards creatures with shells. When one considers how many soft-bodied creatures exist in the world's ecosystems, and how rarely they are preserved, we realize how poor our picture of the past really is. This is especially true of the "dawn" of complex life in the Cambrian period, just over 500 million years ago. Something 75% of the record is made up of the various species of trilobites, and most of the rest are sponge-like archaeocyathids and brachiopods (simple bivalved creatures which are not as "advanced" as clams). Although we know that plenty of soft-bodied forms existed, they have not been preserved, except in a precious few places.

One of these is the Burgess Shale, in British Columbia. The shale accumulated as masses of mud slid into oxygen-poor water. The organisms living in the environment were killed immediately, as were the scavengers and microbes that would have consumed them. The outcrops were discovered by Charles Walcott in 1909, and over the years tens of thousands of specimens have been collected and analyzed. The rocks were full of diverse and sometimes bizarre species that would have otherwise been lost to all time (see this article for examples).

The Burgess Shale is high on a ridge in the Canadian Rockies, and it is a tough six mile hike to the quarry. As a World Heritage Site, and being within a Canadian National Park, access is highly restricted (and believe me, they know when someone is there illegally!). To see the quarry one must go with a conducted tour through the Burgess Shale Geoscience Foundation.

I made the hike in July of 2005, one of the first hikes that year in this cold alpine environment. The sun played hide and seek with the clouds, and rain occasionally threatened (I have the distinct impression that that situation occurs just about every day up there). Glacier Lilies were everywhere, providing a great deal of color along the trail. There were also several steaming piles of grizzly bear poop, so we stayed pretty close together on the trail...

It was a long uphill hike, but after 5 1/2 miles, we passed a sign that let us know we were drawing close.

I walked a little slower than the others, and I paused at the last few steps. Most of the other hikers were not geologists, and were only beginning to understand the importance of this site to paleontology. I gathered my thoughts and emotions, and stepped into the quarry for the first time.

It was still half-filled with snow and ice, but there were plenty of slabs of rock around. Trilobites were all over, and I almost immediately found a delicate sponge fossil. The others gathered at the far end of the quarry, so I walked over.

The foundation knows that random searching in the quarry will not reveal some of the rare creatures, so they keep some pretty decent samples in the red lockbox on the site. Gazing at the specimens, I realized all over again what a wondrous treasure this site this really is for paleontologists.

Collecting of course is not allowed here, but we were allowed to search among the slabs for fossils that we could "own" for ourselves through the magic of digital imagery. I quickly found a nicely preserved Haplophrentis, a primitive mollusk related to snails and clams.

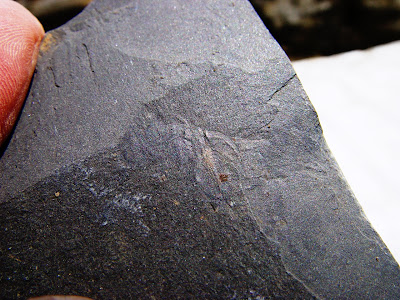

My favorite find was a complex little Marrella species, which is actually the most commonly found fossil in the Burgess Shale. It was the most delicate fossil I've ever found. And hard to photograph!

I tried photographing the fossil from a couple of angles. The brown spot is a stain of fluids that escaped when the organism died. In case you are wondering, no, the specimen didn't "accidently" fall into my pocket. I put it in the pile next to the big red box, so look for it if you ever get up that way.

If you are having difficulty making out the specimen in the pictures above, check out the reconstruction in the picture below to get an idea of the complexity of the little creature. Something close to 180 species of creatures have been found in the shale, and perhaps only 2% would have been preserved in Cambrian sediments anywhere else in the world. The fossil record certainly has a bias that favors animals with hard shells or skeletons.

|

| Marrella splendens Source: http://burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/en/fossil-gallery/view-species.php?id=80&m=3& |

Emerald Lake, thousands of feet below, really looked more turquoise in color, due to the fine clay particles suspended in the water. Glaciers are still carving these mountains.

After about ten hours and 12 miles on steep trails, I arrived back at the parking lot, tired but happy. It was indeed a place worthy of a geological pilgrimage, and easily made my top-ten list of the most splendid places I've ever stood.Number 7: Gubbio Italy, and the Dinosaur Killer (from April 28, 2014)

It's not always easy, but travel whenever you can. See as much of the world as possible. I passed on both New Zealand and Hawaii three decades ago for reasons that seem trivial today. I didn't go overseas until 2001, but my life since then has been enriched in ways that I can barely comprehend. Few of us have resources enough to just leave and go somewhere, but there are sometimes cheap alternatives...like a geology field class! Yes, you have to work and stuff, but you will see wonderful things, and you'll be traveling with interesting people.

Number seven on my list of most incredible places is Gubbio, in the Umbrian Province of Italy, between Rome and Florence. What's not to like about Gubbio? It has castles, monasteries, medieval fortresses, Roman arenas, plus active faults and beautiful mountains (the Apennines). Plus one of the most significant geologic outcrops in the world (more on that a moment).

Back in 2007, we conducted a joint anthropology/geology field studies journey through Italy and Switzerland. I had never been to Italy before, so I had a lot of book learning to accomplish before I could lead students in mastering of the geology of the country. And because I had never been there, we had a tour company make the logistical arrangements. They had a canned tour which visited all the famous sites (the Colosseum! the Leaning Tower of Pisa!) and it was sometimes a bit tricky to see some of the important geology (although Pompei was a stunning exception; the trip included a hike to the summit of Vesuvius as well as a tour of the ruins). On the day that we drove from Rome to Florence, there was a scheduled visit to the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi.

I suppose that some people would have preferred to see the church, but we had noticed that it wouldn't be much of a diversion off our route to see Gubbio instead. It lies east of the main highway high in the Apennines Mountains, the nearly thousand kilometer range that runs down the boot length of the Italian peninsula. The mountains have risen in response to compressive forces related to a convergent boundary in the Mediterranean Sea. In the vicinity of Gubbio, late Mesozoic and early Cenozoic limestone layers have been lifted high into a mountain ridge. In more recent time, faulting formed the valley containing Gubbio. The downdropped crust is called a graben. The eroded fault scarp above the town is called a triangular facet (much of the town is built on the fault surface; see the top picture). That the faults are still active has been shown in dramatic manner, as several deadly earthquakes have shaken the region in recent decades (one of them severely damaged the Basilica of St. Francis in 1997; the L'Aquila quake in 2009 killed 300 people and resulted in some geologists going to prison).

Gubbio has been a crossroads on the Italian peninsula for thousands of years, and numerous cultures have controlled it at one time or another. Its origin dates back to at least the Bronze Age, and some tablets discovered there contain the most extensive known examples of the Umbrian language. The Romans invaded in the 2nd century BCE, and the Roman theater/arena is the second largest known.

The city became powerful and changed hands often during the Medieval period, being on the main transportation routes of the time, but today it is sort of a backwater town, retaining a great deal of its Medieval heritage, including defensive walls, castles, monasteries and churches. But as interesting as these things were, we were there for something else.

The canyon leading down into the town of Gubbio is called the Bottacioni Gorge, and it cuts deeply into the Cretaceous and Paleogene limestone deposits of the Apennines Mountains. In the late 1970s, the father and son team of Luis and Walter Alvarez were here trying to gain some insight on the rate of extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous period, the mass extinction event that did in the dinosaurs about around two-thirds of the species of life on Earth at the time. They decided to test the marine sediments for concentrations of iridium, an element rare on Earth, but relatively more abundant in meteorites. The values were small, a few parts per trillion, and it was hoped that they might provide data on the rate of sedimentation across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary (or the Cretaceous-Tertiary K/T boundary).

They got a big surprise. A clay layer at the boundary exposed in the Bottacioni Gorge spiked at around 3,000 parts per trillion, a huge number. In the years that followed, a similar iridium-enriched clay layer was discovered at numerous sites around the world, and researchers soon suggested that a gigantic asteroid perhaps 6 or 7 miles across hit the planet and ultimate caused the extinction of the dinosaurs and other large creatures.

And here we were, ready to lay our hands on the epic moment recorded in the rock when the way was cleared for mammals to take over terrestrial ecosystems on planet Earth. Except there were a few minor problems. For one, we didn't exactly know precisely where it was. And we didn't know if the spot would be marked or if there would be room to park a bus. And though it seems a minor issue, there were 35 people on the trip, and we didn't know where we were going to eat lunch (as all field trip veterans know, the two most important issues are "where and when do we eat?" and "where is the next bathroom?"). I had figured out that the spot was about 2 kilometers upstream from Gubbio, and that there was some kind of old medieval water canal close by.

So I was on pins and needles watching for the outcrop. The first problem cropped up on the edge of Gubbio. The sign on the road quite clearly said "no buses". Our Italian bus driver solved that problem in fine Italian style by ignoring it and driving right on past. We headed up the gorge, rounded a bend, and there was the canal, but I noted with a sinking heart that we had already passed the outcrop on the narrow road, which was pretty much not appropriate for buses (which is what the sign said, I think...). We drove for an interminable number of kilometers up the canyon (I figured about 80 kilometers, but the reality was probably 10), where the driver found a pullout that might be big enough to turn the bus around in.

Those of you who've seen the Austin Powers chase scene where he has a bit of trouble turning a golf cart around will appreciate what our bus driver did on that mountain road with a narrow pullout and a steep canyon wall. This wasn't a Y-turn. This was a Spiro-graph turn, for those of you who remember that toy. Back and forth for what felt like an hour, but was probably more like five minutes. But it finally happened and we headed back down the canyon.

The outcrop containing the iridium layer was in fact marked with a metal placard and an interpretive sign. We gathered around to have a look.

It was not unexpected I suppose that there would be precious little of the clay layer left at the site. Souvenir hunters have produced a huge cavity in the rock, but still, it was a great moment to lay one's hand on the surface where by most accounts, the dominance of the world by the dinosaurs ended. Medieval stories abound of brave knights sallying forth to slay dragons, but it seems the deed was done some 65 million years before we arrived on the planet.

One could see the drill holes left in the rock by the researchers. It is amazing that such a modest outcrop could contain a few atoms of a substance that could reveal a clue towards solving one of the greatest mysteries of the geologic sciences.

Now about the lunch and bathrooms issue. We had been driving for hours and people were getting hungry and, um, uncomfortable. It turned out that there was a single business in the Bottacioni Gorge, but it happened to be a restaurant, and the owner was quite happy to have a crowd of hungry geologists descend on his establishment. He's been catering to geologists for decades as it turns out, enough so that we were asked to sign the geologists register that was first signed by the Alvarez and his assistants!

And the food? By all accounts, the pasta and mushroom dish was the finest lunch we had on our entire journey. It was delicious! If you ever have the chance to visit the Gubbio locality, plan on eating at the Ristorante Bottacioni.

Number Six: Pu'u O'o, Big Island of Hawai'i (From May 2, 2014)

Yes, Hawai'i gets two spots on my top ten list of the most incredible places I've ever stood. A few days ago I talked about my wonderful adventure in the swamps of the Alaka'i Plateau on Kaua'i, but today we'll hear about the Big Island, and the rather incredible volcano there that has been erupting continuously now for thirty-one years, since 1983. The ongoing eruption of Kilauea and its satellite vent Pu'u O'o is the longest known period of activity in the history of the volcanoes of Hawai'i.

It was June of 2002 when I reached the Hawaiian Islands for the first time in my life. I had spent the first fifteen years of my academic career learning to teach and ignoring any kind of writing or research, but I finally decided to submit an abstract and give a presentation at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science on the Big Island. I anxiously watched the lava flow reports for months ahead of time, but little was happening with the volcano. It was essentially a time of simmering around the summit region of Pu'u O'o, and any chance of seeing active lava flows would require miles of hiking over practically impenetrable forest and rock exposures.

Then, in an incredible moment of good timing, the May 12th Mother's Day Flow began, and a huge river of lava began to make its way down the south flank of Kilauea. In a matter of weeks it was approaching the final pali (gigantic fault scarp/cliff) before reaching the coastal plain. On the day my flight landed in Hawai'i, the U.S. Geological Survey posted the picture you can see below (in case you have trouble with the perspective, the cliff in the photo is several hundred feet high. I was beside myself with anticipation. The lava was only a mile away from the end of the highway!

|

| Source: U.S. Geological Survey |

Still, one has to be careful. One never knows when a fault might suddenly appear on a park highway (note the sign above). And strangely, in the way that all signs have a story, this was a place where a lava flow once burst out right onto the highway, in front of a very surprised volcanologist!

I was in for a crushing disappointment, though. The advancing lava flow had started the biggest forest fire in Hawaii's history. The road providing access to the lava flow was closed for firefighting operations. I was devastated to say the least. Here I was, on the island for the first time in my life, the lava was easily accessible, and I wasn't going to get to see it...

I didn't know about Hawaiian attitudes towards fighting forest fires, though. Here in California fires are a serious business with an "all hands on deck" approach that has firefighters working night and day until the fire is out. Since this fire was not threatening homes or structures, the firefighting teams knocked off at five o'clock and went home for a beer or something. They opened the road! We joined the long traffic jam in a headlong rush down Chain of Craters Road to the beginning of the "trail" to the lava flow. I was wondering what kind of parking lot they had down there on the old lava flows. I soon found out. There wasn't one.

What happened instead is that one drove to the end of the road, did a U-turn, and then drove back up the road until a space appeared to park in. As we drove back up the road, my hike went from one mile, to two, to three. At least those extra miles weren't on rugged lava flows. I got out and quickly started down the road, filled with a sense of anticipation that I suspect only a fellow geologist can understand.

The "trail" was a set of yellow markers glued to the surface of the lava flow. It was something of a relief that the flows were of the smooth pahoehoe lava instead of the very rugged a'a type. I made good time running (yes, running; don't tell my wife about this) towards the lava flows. I was quickly becoming aware of the reason Hawaiian lava flows are best seen in dusk or at night. The incandescent rock is easily obscured in bright sunlight. At night, it turns into a light show.

I soon realized that I had active lava flows on three sides of me, and small fires were burning where the lava was engulfing shrubs. And then I was there at the leading active edge of the flow. It was one of the most unusual moments of my life. There just isn't anything that quite prepares you for standing inches away from molten basalt. It wasn't scary so much as it was hypnotic. I couldn't help staring at it in wonderment. This might be hard for some of you to believe, but for a few moments I forgot I was holding a camera and a video recorder. That didn't last long, because in mere minutes I was snapping away.

This was one of my first journeys with a digital camera, so I had a bit of trouble getting sharp pictures in the dim light from sheer ignorance of the capabilities of my camera. I got a few half decent shots of one of the most awesome events I had ever witnessed. Oh, but how I wish I had been carrying the camera I have today. I guess I'll just have to wait for the next big eruption!

When I was younger, I had a preoccupation with the idea of being the only human ever to stand in a particular place. I knew that most inhabited parts of the world had been trod by generation after generation of people, so I wondered how many times in my life I had actually put my feet on a spot that no other person had ever stepped. After my adventure in June of 2002, I know that I was the only person in all of human existence who ever stepped on a small plot of rock at the leading edge of an active lava flow. The rock had only existed for a few minutes when I stepped onto it while preparing for a picture. It was engulfed a few short moments later by the advancing basalt.

Look for the other five incredible places in the next post!

1 comment:

I’m an ex-geo, as ex as one can be anyway. I still look at outcrops and road cuts, my wife still tells me to watch the road when driving, not the rocks, but I quit earning a living from precious metals exploration in 1986. But I have to say standing on billion+ year old lava in Canada and then fresh stuff melting your shoe rubber in Hawaii was quite a thrill. Fresh rock!

When we visited years ago, the Park rangers prevented anybody from going past the lava-blocked end of the road. The simple solution was wait for the rangers to go off duty around 5PM then everybody made a break for the hot surface running lava. We looked for smoke, vegetation that was being engulfed by surface flows and lobes. I swiped a wooden mop handle from our Timeshare, wired it to my old Estwing rock hammer and dipped the hammer into the lava. I still have that lava cast. Took hours for it to cool enough to put in my backpack. My wife had nightmares for weeks of us falling thru the lava and apparently some tourists later that month did die when the lava shelf they were standing on collapsed.

Post a Comment