There was a time not all that long ago when there was a part of the United States mainland that was still considered terra incognito. It was in 1948 that National Geographic explored this region and called it not a tour, but an expedition, complete with jeeps and supply caches, and explorers who gave new names to features, even though many of them already had been named by the resident ranchers.

Kodachrome Basin State Park (once called Thorley's Pasture) in southern Utah showed up at the end our our 40 mile gravel road journey through what I called a land of strange standing stones (it's also accessible from the north by a paved road out of Bryce Canyon National Park). For the second time in a day we were treated to the strange sight of vertical pillars of stone, but these had an origin quite unique from the spires along Cottonwood Wash Road. It's an origin so unique that geologists haven't quite decided what it actually is.

The spires, called sedimentary pipes, are composed mostly of a mix of sediment from the lower

members of the Carmel Formation that have penetrated into the overlying Entrada Sandstone. There are more than five

dozen of them in and around the park, ranging in height from 6

feet (2 m) to 170 feet (52 m). They are composed of a more highly cemented

rock, having been exposed as the surrounding sediments were eroded away It has been suggested that they are the result of hot

spring activity, and that they might have been pathways for geysers

(some have suggested that the park is sort of a Yellowstone in reverse).

This is an intriguing and imaginative idea, but what was the source of

the heat? There are no magma intrusions in the immediate region, and in

other parts on the Colorado Plateau where intrusions do occur, such

pipes aren't found.

Another possible explanation is that the pipes are liquefaction

features, places where water rushes towards the surface from saturated

layers below during the shaking from earthquakes. I like this

explanation, since there are some major fault zones just a

few miles away. But researchers say there is a time problem. They say that the pipes are very old features: they don't

penetrate the overlying Henrieville sandstone, and are therefore

probably Jurassic or early Cretaceous in age. The faults in the region

didn't become active until less than about 15 million years ago. Maybe.

The most recent hypothesis is that the pipes formed from lenses of

groundwater trapped in sabkha deposits, layers of evaporites like salt

or gypsum along arid environment shorelines, which formed the Paria

member of the Carmel formation. As younger sediments were laid down on

top of the older layers, the pressure grew in the groundwater deposit,

and water squeezed out, following the path of least resistance,

generally upwards. This model is interesting, but has it been seen in other settings? Some of the petroleum geologists that have traveled with us find this to be a plausible explanation.

But aren't mysteries great? Like the origin of the Grand Canyon, science thrives on unanswered questions. It's a fascinating place to visit and explore.

The sediments in which the pipes occur are mostly members of the Jurassic Entrada formation, which is

responsible for some spectacular scenery in other parts of the Colorado

Plateau, most notably at Arches National Park and Goblin Valley State

Park. The bright orange layers are the Gunsight Butte member, while the

high white and red striped cliffs are the Cannonville member, and the

light tan layers are the Escalante member. The highest cliff ramparts

are composed of Cretaceous Henrieville and Dakota sandstones, last seen at Grosvenor Arch.

For more information...

Get the park brochure here: http://static.stateparks.utah.gov/docs/kbspNewsBrochure.pdf

An excellent resource: Baer, J. and R. Steed. 2010. Geology of Kodachrome Basin State Park, Kane County, Utah. In Sprinkel, D.A. et al (eds.), Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments, Utah Geological Association Publication 28, 3rd edition. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Association, 467-482.

Showing posts with label Entrada Sandstone. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Entrada Sandstone. Show all posts

Friday, June 27, 2014

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Yeah, I'm Still Here (and there, and everywhere): SUPER MOON!

Hey world! I'm still here...and there...and it feels like everywhere, and we are having a great time exploring the geology of the Colorado Plateau. This has been one of our cooler trips ever, with spring-like temperatures (and windstorms), so we are enjoying it as much as possible. Since the last post, we've been to Grand Canyon, Cedar Mesa, Mesa Verde, Arches, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef and lots of other wonders. We are actually just two more days from being home.

I know the SUPER MOON was overblown, as usual, but a full moon rising at Arches National Park is nothing to sneer at. It was gorgeous, and if you want to see it supermoon style, you just up the zoom on the camera, and voila!

A morning or two later, we could watch the moon setting among the Entrada Sandstone cliffs...

Lots of pictures, lots of adventures in geology to talk about. We'll see you in a few days!

I know the SUPER MOON was overblown, as usual, but a full moon rising at Arches National Park is nothing to sneer at. It was gorgeous, and if you want to see it supermoon style, you just up the zoom on the camera, and voila!

A morning or two later, we could watch the moon setting among the Entrada Sandstone cliffs...

Lots of pictures, lots of adventures in geology to talk about. We'll see you in a few days!

Friday, October 12, 2012

The Abandoned Lands...A Journey Through the Colorado Plateau: A day in the canyonlands, Part 2

In the last post, we saw the sun rise over the Canyonlands region of the Colorado Plateau, an area that includes Arches and Canyonlands National Parks and Dead Horse Point State Park. We saw all three on this one extraordinary day.

We woke up and Devils Garden Campground in Arches, and in the relative cool of the morning we followed the trail out of Devils Garden to see the largest natural span in existence: Landscape Arch. At 290 feet, the span is as long as a football field.

If you haven't ever seen Landscape Arch, you should bump it up to the top of your bucket list, because I don't think it is going to persist much beyond our collective life times. Since 1991, slabs measuring 30, 47 and 70 feet have dropped off the thinnest part of the arch. The trail under the arch was closed years ago for fear of rocks falling on visitors. The folks at Wikipedia think that it might mean there is less weight being supported by the arch, but I think that the math is increasingly working against the continued existence of the sandstone span.

Some of the students who were on the trip might not remember the moon lurking underneath the arch that day. I'm cheating just a little, pulling up my favorite shots from the 2008 trip, since I actually walked a different trail that morning. I was headed to Pine Tree Arch, which is on a short spur trail off the walk to Landscape.

Because of the unique geological circumstances of the Paradox Basin, the park contains the highest concentration of arches on the planet. Most of them occur in the Jurassic Entrada Sandstone, a relatively uniform dune sand that formed in a tropical or equatorial coastal region. The Entrada lies above salt layers that developed in the Paradox basin (a large isolated bay complex that occasionally was cut off from the ocean and dried up) in late Paleozoic time. Salt deforms easily under pressure, and has pushed the overlying rocks into a series of anticlines (upward pointing folds in the rock). When the salt began to interact with groundwater, the salt dissolved and the top of the anticline collapsed inwards, stressing the overlying Entrada, and causing a series of parallel joints to form, like those in the picture above, at the start of the Landscape Arch Trail.

Once the fins develop, precipitation is directed preferentially into the sand-filled joints and fractures, and the constant soaking of the sandstone at the base of the fin causes the solid rock to lose cement at a higher rate than the higher parts of the fin. Eventually a small opening occurs, and slabs of rock fall out, enlarging the arch over time. The arches grow until they collapse, an event that is fairly common, even in human times of reference. Several dozen arches have collapsed since 1971 according to some web sources, but I can't find any original confirmation for the number (that's out of 2,000 arches in the park). It's not that we are running out of arches, though; new ones are forming too.

Pine Tree Arch is an attractive little span with a nice view through the opening. One thing about Landscape Arch is the difficulty of getting a good angle on the sky. There is a cliff behind Landscape, and the closed trail prevents access for views upward. I found Pine Tree far less crowded and more intimate, even though it was only a few hundred feet from the main trail.

We finished our hike and returned to the vans. We headed to the Windows Section of the park, and the heat...well the heat descended on us like a blanket. Just look how the gang fought for the pitiful amount of shade at our lecture stop!

Next, an Indiana Jones adventure! This is a continuing series about what I've called the Abandoned Lands of the Colorado Plateau. It's kind of hard to be describing a very crowded national park as an abandoned place, but it was abandoned already by the Native Americans, the original ranchers, the uranium miners, and when the price of oil becomes prohibitively expensive, I worry it will be abandoned by our society as well. In the meantime, it is a place of beauty and inspiration.

We woke up and Devils Garden Campground in Arches, and in the relative cool of the morning we followed the trail out of Devils Garden to see the largest natural span in existence: Landscape Arch. At 290 feet, the span is as long as a football field.

If you haven't ever seen Landscape Arch, you should bump it up to the top of your bucket list, because I don't think it is going to persist much beyond our collective life times. Since 1991, slabs measuring 30, 47 and 70 feet have dropped off the thinnest part of the arch. The trail under the arch was closed years ago for fear of rocks falling on visitors. The folks at Wikipedia think that it might mean there is less weight being supported by the arch, but I think that the math is increasingly working against the continued existence of the sandstone span.

Some of the students who were on the trip might not remember the moon lurking underneath the arch that day. I'm cheating just a little, pulling up my favorite shots from the 2008 trip, since I actually walked a different trail that morning. I was headed to Pine Tree Arch, which is on a short spur trail off the walk to Landscape.

Because of the unique geological circumstances of the Paradox Basin, the park contains the highest concentration of arches on the planet. Most of them occur in the Jurassic Entrada Sandstone, a relatively uniform dune sand that formed in a tropical or equatorial coastal region. The Entrada lies above salt layers that developed in the Paradox basin (a large isolated bay complex that occasionally was cut off from the ocean and dried up) in late Paleozoic time. Salt deforms easily under pressure, and has pushed the overlying rocks into a series of anticlines (upward pointing folds in the rock). When the salt began to interact with groundwater, the salt dissolved and the top of the anticline collapsed inwards, stressing the overlying Entrada, and causing a series of parallel joints to form, like those in the picture above, at the start of the Landscape Arch Trail.

|

| The raven apparently supports an alternate hypothesis of arch formation. |

Pine Tree Arch is an attractive little span with a nice view through the opening. One thing about Landscape Arch is the difficulty of getting a good angle on the sky. There is a cliff behind Landscape, and the closed trail prevents access for views upward. I found Pine Tree far less crowded and more intimate, even though it was only a few hundred feet from the main trail.

We finished our hike and returned to the vans. We headed to the Windows Section of the park, and the heat...well the heat descended on us like a blanket. Just look how the gang fought for the pitiful amount of shade at our lecture stop!

Next, an Indiana Jones adventure! This is a continuing series about what I've called the Abandoned Lands of the Colorado Plateau. It's kind of hard to be describing a very crowded national park as an abandoned place, but it was abandoned already by the Native Americans, the original ranchers, the uranium miners, and when the price of oil becomes prohibitively expensive, I worry it will be abandoned by our society as well. In the meantime, it is a place of beauty and inspiration.

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

I Guess "Fujicolor Basin" Just Didn't Have That Ring To It: Exploring Kodachrome Basin State Park

I'm not a real fan of corporate name sponsorship. I simply can't keep up with the names of Candlestick Park and whatever they're calling the stadium where the Lakers play in Los Angeles. When one hears the name of the little-known state park in Utah, it sounds like another case of corporate sponsorship gone crazy. But as I understand it, the story of the naming of Kodachrome Basin State Park was a bit more nuanced.

It's funny how a name can change the meaning and significance of a place. A hundred years ago, only a few ranchers and local Native Americans had ever even seen Kodachrome, and the ranchers referred to it as Thorny or Thorley's Pasture (I'm operating off dim memory here), and the beautiful valley was quite literally unknown to anyone from outside the region. In the late 1940's an exploration party from the National Geographic Society came through the region (imagine still exploring the United States only half a century ago!), and they were impressed with the scenery. They used their influence to rename nearby Butler Arch for their director (the arch is now called Grosvenor Arch). They gave the basin its name for the vivid color for a new bright film variety from Kodak. The article in National Geographic brought a lot of attention to the region, and tourists started seeking it out.

I must say I don't get corporate thinking sometimes either. Apparently Kodak was not happy with the copyright infringement, so when Utah sought to make a state park out of the basin, they called it Chimney Rock State Park. Kodak finally wised up and realized what a free marketing opportunity they had, and consented to calling the park Kodachrome Basin. Over the years they have provided some support to the park. The park has outlasted the product; Kodak produced the last roll of Kodachrome film in 2009, and the company is struggling to survive in the digital age.

The park has two main attributes: the colorful Jurassic sedimentary rocks, and the strange columnar towers called sedimentary pipes. The sediments are mostly members of the Entrada formation, which is responsible for some spectacular scenery in other parts of the Colorado Plateau, most notably at Arches National Park and Goblin Valley State Park. The bright orange layers are the Gunsight Butte member, while the high white and red striped cliffs are the Cannonville member, and the light tan layers are the Escalante member. The highest cliff ramparts are composed of Cretaceous Henrieville and Dakota sandstones.

Lower parts of the basin expose Jurassic Carmel formation, most notably the Winsor member. The odd pipes occur mostly in the Winsor member, and the overlying Gunsight member of the Entrada.

The sedimentary pipes are one of those interesting mysteries that crop up in geology every so often. They are composed mostly of a slurry mix of sediment from the lower members of the Carmel, and penetrate the Entrada. There are around four dozen of them in and around the park, and they range in height from 6 feet (2 m) to 170 feet (52 m). They are composed of more highly cemented rock, so as the sediments are eroded away from around them, they end up standing out. It has been suggested that they are the result of hot spring activity, and that they might have been pathways for geysers (some have suggested that the park is sort of a Yellowstone in reverse). This is an intriguing and imaginative idea, but what was the source of the heat? There are no magma intrusions in the immediate region, and in other parts on the Colorado Plateau where intrusions do occur, such pipes aren't found (that I know of).

Another possible explanation is that the pipes are liquefaction features, places where water rushes towards the surface from saturated layers below during the shaking from earthquakes. I've liked this explanation in the past, since there are a few major fault zones just a few miles away. But researchers say there is a time problem. The latest studies suggest that the pipes are very old features: they don't penetrate the overlying Henrieville sandstone, and are therefore probably Jurassic or early Cretaceous in age. The faults in the region didn't become active until less than about 15 million years ago. I still like this explanation though...everyone knows that one's favorite hypothesis has to be the right one...I think.

The most recent suggestion is that the pipes formed from lenses of groundwater trapped in sabkha deposits, layers of evaporites like salt or gypsum along arid environment shorelines, which formed the Paria member of the Carmel formation. As younger sediments were laid down on top of the older layers, the pressure grew in the groundwater deposit, and water squeezed out, following the path of least resistance, generally upwards. This model has the virtue of being supported by most of the evidence...but I repeat the end of the last paragraph.

The park is a pleasant place to explore. In addition to the colors and unusual pipes close at hand, there are beautiful vistas to be had. On our reconnaisance trip a few weeks back we hiked out to Shakespeare Arch in a remote corner of the park. The short trail included panoramas of the White Cliffs to the southwest, the high cliffs of Navajo sandstone found around Carmel Junction and Kanab.

To the west, the pink strip on the horizon is the Claron formation, the Pink Cliffs of Bryce Canyon National Park.

We could also look up the slope to Kodachrome Basin itself. All in all a very colorful landscape.

The state of Utah has worked hard to make Kodachrome a destination for campers. The small 28 unit campground has flush toilets and showers. They sell firewood. And get this: when we arrived at our campsite, it looked like someone had raked our campsite. Feng shui in the wilderness! There is a small general store, a few rental cabins, and a new visitor center. If you have a large group, you can reserve one of two group campsites: the older Oasis site has been a favorite of ours for many years. The Arches site is newer, but is in an isolated corner of the park, with fewer facilities. I've had many commenters say that Kodachrome is their favorite campground on the Colorado Plateau. I put it near the top of my list, too.

We'll be stopping at Kodachrome during the AAPG tour that I am leading in July. If you want to join us, get the information here.

Get the park brochure here: http://static.stateparks.utah.gov/docs/kbspNewsBrochure.pdf

An excellent resource: Baer, J. and R. Steed. 2010. Geology of Kodachrome Basin State Park, Kane County, Utah. In Sprinkel, D.A. et al (eds.), Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments, Utah Geological Association Publication 28, 3rd edition. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Association, 467-482.

It's funny how a name can change the meaning and significance of a place. A hundred years ago, only a few ranchers and local Native Americans had ever even seen Kodachrome, and the ranchers referred to it as Thorny or Thorley's Pasture (I'm operating off dim memory here), and the beautiful valley was quite literally unknown to anyone from outside the region. In the late 1940's an exploration party from the National Geographic Society came through the region (imagine still exploring the United States only half a century ago!), and they were impressed with the scenery. They used their influence to rename nearby Butler Arch for their director (the arch is now called Grosvenor Arch). They gave the basin its name for the vivid color for a new bright film variety from Kodak. The article in National Geographic brought a lot of attention to the region, and tourists started seeking it out.

I must say I don't get corporate thinking sometimes either. Apparently Kodak was not happy with the copyright infringement, so when Utah sought to make a state park out of the basin, they called it Chimney Rock State Park. Kodak finally wised up and realized what a free marketing opportunity they had, and consented to calling the park Kodachrome Basin. Over the years they have provided some support to the park. The park has outlasted the product; Kodak produced the last roll of Kodachrome film in 2009, and the company is struggling to survive in the digital age.

The park has two main attributes: the colorful Jurassic sedimentary rocks, and the strange columnar towers called sedimentary pipes. The sediments are mostly members of the Entrada formation, which is responsible for some spectacular scenery in other parts of the Colorado Plateau, most notably at Arches National Park and Goblin Valley State Park. The bright orange layers are the Gunsight Butte member, while the high white and red striped cliffs are the Cannonville member, and the light tan layers are the Escalante member. The highest cliff ramparts are composed of Cretaceous Henrieville and Dakota sandstones.

Lower parts of the basin expose Jurassic Carmel formation, most notably the Winsor member. The odd pipes occur mostly in the Winsor member, and the overlying Gunsight member of the Entrada.

The sedimentary pipes are one of those interesting mysteries that crop up in geology every so often. They are composed mostly of a slurry mix of sediment from the lower members of the Carmel, and penetrate the Entrada. There are around four dozen of them in and around the park, and they range in height from 6 feet (2 m) to 170 feet (52 m). They are composed of more highly cemented rock, so as the sediments are eroded away from around them, they end up standing out. It has been suggested that they are the result of hot spring activity, and that they might have been pathways for geysers (some have suggested that the park is sort of a Yellowstone in reverse). This is an intriguing and imaginative idea, but what was the source of the heat? There are no magma intrusions in the immediate region, and in other parts on the Colorado Plateau where intrusions do occur, such pipes aren't found (that I know of).

Another possible explanation is that the pipes are liquefaction features, places where water rushes towards the surface from saturated layers below during the shaking from earthquakes. I've liked this explanation in the past, since there are a few major fault zones just a few miles away. But researchers say there is a time problem. The latest studies suggest that the pipes are very old features: they don't penetrate the overlying Henrieville sandstone, and are therefore probably Jurassic or early Cretaceous in age. The faults in the region didn't become active until less than about 15 million years ago. I still like this explanation though...everyone knows that one's favorite hypothesis has to be the right one...I think.

The most recent suggestion is that the pipes formed from lenses of groundwater trapped in sabkha deposits, layers of evaporites like salt or gypsum along arid environment shorelines, which formed the Paria member of the Carmel formation. As younger sediments were laid down on top of the older layers, the pressure grew in the groundwater deposit, and water squeezed out, following the path of least resistance, generally upwards. This model has the virtue of being supported by most of the evidence...but I repeat the end of the last paragraph.

The park is a pleasant place to explore. In addition to the colors and unusual pipes close at hand, there are beautiful vistas to be had. On our reconnaisance trip a few weeks back we hiked out to Shakespeare Arch in a remote corner of the park. The short trail included panoramas of the White Cliffs to the southwest, the high cliffs of Navajo sandstone found around Carmel Junction and Kanab.

To the west, the pink strip on the horizon is the Claron formation, the Pink Cliffs of Bryce Canyon National Park.

We could also look up the slope to Kodachrome Basin itself. All in all a very colorful landscape.

The state of Utah has worked hard to make Kodachrome a destination for campers. The small 28 unit campground has flush toilets and showers. They sell firewood. And get this: when we arrived at our campsite, it looked like someone had raked our campsite. Feng shui in the wilderness! There is a small general store, a few rental cabins, and a new visitor center. If you have a large group, you can reserve one of two group campsites: the older Oasis site has been a favorite of ours for many years. The Arches site is newer, but is in an isolated corner of the park, with fewer facilities. I've had many commenters say that Kodachrome is their favorite campground on the Colorado Plateau. I put it near the top of my list, too.

We'll be stopping at Kodachrome during the AAPG tour that I am leading in July. If you want to join us, get the information here.

Get the park brochure here: http://static.stateparks.utah.gov/docs/kbspNewsBrochure.pdf

An excellent resource: Baer, J. and R. Steed. 2010. Geology of Kodachrome Basin State Park, Kane County, Utah. In Sprinkel, D.A. et al (eds.), Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments, Utah Geological Association Publication 28, 3rd edition. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Association, 467-482.

|

| Shakespeare Arch is one more attraction in an already attractive place. It's at the end of pleasant half mile hike. |

Monday, November 28, 2011

Vagabonding Across the 39th Parallel: Sun and Rock in Arches National Park

Last summer we set out on a vagabonding journey that roughly followed the 39th Parallel across the western states of Nevada, Utah and Colorado. By vagabonding, I refer to the set of loose rules we followed to not plan more than a day or two in advance, and try to see as many new sights as we could see. We ultimately made it to Rocky Mountain National Park, and now after 10 days on the road, we were headed west, slowly returning home to California. Our winding road brought us to the town of Moab, Utah, and Arches National Park. We were now on the Colorado Plateau, a vast area of the earth's crust that was stable for hundreds of millions of years, but in recent geologic time has been uplifted and deeply eroded by the Colorado River and her tributaries.

I've been to Arches National Park a great many times, but almost always with a large group of students. A group necessitates some serious planning, and our trips usually include the same three places: a hike to Delicate Arch for the sunset, a hike to Double Arch, and a hike to Landscape Arch, the largest in the park (and probably in the world). On this particular day, our new experience was stopping and sitting at one of the less iconic viewpoints. Literally sitting, for a rather long time. We had a picnic dinner, and just experienced the desert while the sun set behind us.

Before settling in, we made a quick circuit past the La Sal Mountains overlook and the Windows Section. The La Sal Mountains are outside of Arches National Park, but provide a spectacular backdrop to arches and fins that make up most of the scenery in the park. The mountains have an unusual origin. They are not quite volcanic in origin (although volcanoes almost surely existed here, but have been eroded away), but instead are formed of intrusive rock that reached shallow depths in the crust, wedging and bulging up the sedimentary layers that lay above the molten rock. The intrusions are called laccoliths. The mountains rise to 12,000 feet, and are often snow-covered, even in early summer.

The Windows Section contains several large arches, including Double Arch, made famous by the opening scenes of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. There is no deep cave up in the alcove, and no Coronado's Cross, though. Just a spectacular double arch. It's big; click on the photo below and look for the people walking under the arch.

The Windows Section is a good place to learn the stratigraphy of Arches National Park (see the picture below). There are three important sedimentary layers that are fundamental to the scenery, all Jurassic in age. The Navajo Sandstone is the preserved remains of a vast dune sea (an erg) that developed along the western edge of the supercontinent Pangea. It makes up much of the spectacular scenery at other parks like Zion and Capitol Reef, but is less visible in Arches. It makes up the lighter-colored layer at the base of the slope in the picture below.

The layers atop the Navajo Sandstone are two members of the Entrada Sandstone: the Dewey Bridge member and the Slickrock member. The Dewey Bridge formed in a tidal flat environment and has variable layers of siltstone and sandstone. It is easily eroded, which allows it to undercut the harder Slickrock member, causing the cliffs and fins in which the arches are developed. It often has a wavy "crinkled" aspect that has led some geologists to speculate that the layer was affected by the nearby impact of an asteroid at Upheaval Dome. The speculation is controversial, but the explanation appeals to me simply on the scale of grandeur and in thinking outside the box.

The cliffs at Arches are made of the Slickrock member of the Entrada Sandstone. The formation preserves sand dunes that developed along the coast of Pangea (much like the Navajo Sandstone). The arches form most often in the Slickrock member. I wrote about the formation of the arches in my series Time Beyond Imagining. Here is a short excerpt:

Arches is an elemental place, as most desert landscapes are. There is sunlight, and there is rock. Everything else is secondary, the plants, the animals, the people. If you are caught in the open on a hot summer day, the elements are perilous. Survival is a crapshoot. In our insulated existence, the crapshoot becomes a source of great beauty, especially as the sun sinks and the searing heat dissipates. The rocks glow, and then slowly fade to darkness.

Our minds see meaning in the random shapes of the rocks, and we make stories of their origin. Some stories involve myths and heroes, while others involve jointing and frost wedging. I enjoy both kinds. What do you see here?

The fire in the sky died away, and stars emerged in the darkness. We gathered our things and drove back into town.

I've been to Arches National Park a great many times, but almost always with a large group of students. A group necessitates some serious planning, and our trips usually include the same three places: a hike to Delicate Arch for the sunset, a hike to Double Arch, and a hike to Landscape Arch, the largest in the park (and probably in the world). On this particular day, our new experience was stopping and sitting at one of the less iconic viewpoints. Literally sitting, for a rather long time. We had a picnic dinner, and just experienced the desert while the sun set behind us.

Before settling in, we made a quick circuit past the La Sal Mountains overlook and the Windows Section. The La Sal Mountains are outside of Arches National Park, but provide a spectacular backdrop to arches and fins that make up most of the scenery in the park. The mountains have an unusual origin. They are not quite volcanic in origin (although volcanoes almost surely existed here, but have been eroded away), but instead are formed of intrusive rock that reached shallow depths in the crust, wedging and bulging up the sedimentary layers that lay above the molten rock. The intrusions are called laccoliths. The mountains rise to 12,000 feet, and are often snow-covered, even in early summer.

The Windows Section contains several large arches, including Double Arch, made famous by the opening scenes of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. There is no deep cave up in the alcove, and no Coronado's Cross, though. Just a spectacular double arch. It's big; click on the photo below and look for the people walking under the arch.

The Windows Section is a good place to learn the stratigraphy of Arches National Park (see the picture below). There are three important sedimentary layers that are fundamental to the scenery, all Jurassic in age. The Navajo Sandstone is the preserved remains of a vast dune sea (an erg) that developed along the western edge of the supercontinent Pangea. It makes up much of the spectacular scenery at other parks like Zion and Capitol Reef, but is less visible in Arches. It makes up the lighter-colored layer at the base of the slope in the picture below.

The layers atop the Navajo Sandstone are two members of the Entrada Sandstone: the Dewey Bridge member and the Slickrock member. The Dewey Bridge formed in a tidal flat environment and has variable layers of siltstone and sandstone. It is easily eroded, which allows it to undercut the harder Slickrock member, causing the cliffs and fins in which the arches are developed. It often has a wavy "crinkled" aspect that has led some geologists to speculate that the layer was affected by the nearby impact of an asteroid at Upheaval Dome. The speculation is controversial, but the explanation appeals to me simply on the scale of grandeur and in thinking outside the box.

The cliffs at Arches are made of the Slickrock member of the Entrada Sandstone. The formation preserves sand dunes that developed along the coast of Pangea (much like the Navajo Sandstone). The arches form most often in the Slickrock member. I wrote about the formation of the arches in my series Time Beyond Imagining. Here is a short excerpt:

"The origin of the park's famous arches (there are hundreds) is tied to the salts of the Paradox Basin. The salt beds are thousands of feet thick, and when placed under pressure, can slowly flow upwards through the overlying rock, forming domes and anticlines (upward pointing folds). Over millions of years, erosion removed thousands of feet of overlying sediment, and the salt was close enough to the surface to be affected by groundwater: it was dissolved away. The tops of the folds collapsed inwards, and the Entrada Sandstone was fractured (jointing) into a series of parallel fins. A large northwest trending anticline crosses the park; most of the arches occur along the flanks of the anticline.The sun was sinking lower towards the horizon. We sat in the silence and ate our sandwiches; a few cars stopped briefly and people stepped out to see what we were looking at, but they were mostly in a hurry to be someplace else.

The top of the fins are exposed to the arid desert climate, where the rock dries quickly following the infrequent storms. At the base of the fins, where the rock is buried by soil and loose sand, the rock may stay moist much longer. This leads to the solution of the cement holding the sandstone together, and the fins start to weather from below. Eventually a small window may open up, and falling slabs of rock enlarge the opening."

Arches is an elemental place, as most desert landscapes are. There is sunlight, and there is rock. Everything else is secondary, the plants, the animals, the people. If you are caught in the open on a hot summer day, the elements are perilous. Survival is a crapshoot. In our insulated existence, the crapshoot becomes a source of great beauty, especially as the sun sinks and the searing heat dissipates. The rocks glow, and then slowly fade to darkness.

Our minds see meaning in the random shapes of the rocks, and we make stories of their origin. Some stories involve myths and heroes, while others involve jointing and frost wedging. I enjoy both kinds. What do you see here?

The fire in the sky died away, and stars emerged in the darkness. We gathered our things and drove back into town.

Sunday, March 6, 2011

My Favorite Geologic Picture: Oh, so many to choose from...(Accretionary Wedge #32)

The Accretionary Wedge for early March is sponsored by Ann's Musings on Geology and Other Things, and we are asked for our favorite geological picture. What a hard choice!

Long before I had a digital camera, I used a particular slide from a trip in the 1980s to introduce my students to the idea of the fascination of geology. It was taken next to one of the most famous photography spots in our national park system, but it is not a picture of the iconic feature. It's the trail leading to it. Delicate Arch of the "Real" Jurassic Park lies just around the corner, and a crowd is often found there, especially at sunset. But I see fewer people stop and consider this scene....

I got into geology in part because of the wonderful journey of imagination that it is; a geologist is a world traveler, and a time traveler. The trail in this picture is formed on a natural break in the rock. Why is the break there?

In Jurassic time 180 and 140 million years ago, tidal flats and coastal sand dunes spread across this part of Utah. The surfaces of the dunes were pathways for all kinds of creatures, from insects to giant lumbering dinosaurs. The walked and crawled on these sands, and later the surfaces were preserved by subsequent layers of windblown sand. The surface later hardened a bit more than the others, and millions of years later, erosion exposed the old sands. A fracture developed along the surface, and the trail-builders of a few decades ago found it a great deal easier to just remove the overlying rock than to carve a new flat surface at great expense. And so it is that during our brief sojourn on the planet, we walk on the same surface, and perceive the significance of that fact. We use our minds to explore strange alien worlds, and yet these are the worlds that existed before ours and which became the raw materials for our own.

Again, practically everyone walks up to Delicate Arch, but there is another arch just a few steps off the trail that provides a stunning view the distant La Sal Mountains, the laccolithic cores of 25 million year old volcanoes. This picture, taken just a few yards from the one above, contains the four elements of ancient human thought: water, earth, fire and sky (the water is in the sky and in the creek below). The essence of earth science...

Again, practically everyone walks up to Delicate Arch, but there is another arch just a few steps off the trail that provides a stunning view the distant La Sal Mountains, the laccolithic cores of 25 million year old volcanoes. This picture, taken just a few yards from the one above, contains the four elements of ancient human thought: water, earth, fire and sky (the water is in the sky and in the creek below). The essence of earth science...Thanks to Ann for sponsoring the Wedge!

UPDATE 8/19/11: Do you need geology-themed photos and images for teaching or research purposes? I have hundreds of geologic images posted at Geotripper Images. Check it out!

Sunday, November 9, 2008

The Real Jurassic Parks: Arches National Park, continued. And an Eminent Threat.

I didn't really mean to leave everyone hanging in the Jurassic during our months-long tour of the geology of the Colorado Plateau, but I am easily distracted by things like work and politics. I want to at least make it out of the Mesozoic era before Thanksgiving, so I am picking up the thread where we left off on Oct. 17 with a visit to Arches National Park.

The stratigraphy of the park is relatively straightforward: the visible scenery mainly includes the Navajo Sandstone, the Dewey Bridge member of the Entrada Sandstone, and the Slickrock member of the Entrada. The Navajo Sandstone has a huge role in the scenery of other parks on the Plateau (see discussions here), but is mostly muted here. It is familiar to park tourists as the "petrified sand dunes" that can seen along the road in the south part of the park, and the very dramatic white rock along the park entrance road. The Dewey Bridge member is a "crinkly" layer of sand, silt and gypsum at the base of many of the arches. The reason for the deformed layers is unclear. One intriguing proposal is that a nearby asteroid impact distorted the layers (Upheaval Dome in Canyonlands National Park is the proposed impact site). Most of the arches occur in the Slickrock member, a cliff-forming layer that is obvious throughout the park.

The origin of the park's famous arches (there are hundreds) is tied to the salts of the Paradox Basin discussed earlier in this post. The salt beds are thousands of feet thick, and when placed under pressure, can slowly flow upwards through the overlying rock, forming domes and anticlines (upward pointing folds). Over millions of years, erosion removed thousands of feet of overlying sediment, and the salt was close enough to the surface to be affected by groundwater: it was dissolved away. The tops of the folds collapsed inwards, and the Entrada Sandstone was fractured (jointing) into a series of parallel fins. A large northwest trending anticline crosses the park; most of the arches occur along the flanks of the anticline.

The top of the fins are exposed to the arid desert climate, where the rock dries quickly following the infrequent storms. At the base of the fins, where the rock is buried by soil and loose sand, the rock may stay moist much longer. This leads to the solution of the cement holding the sandstone together, and the fins start to weather from below. Eventually a small window may open up, and falling slabs of rock enlarge the opening. The largest arch, Landscape, has an opening the length of a football field. Unfortunately, it is so thin and fractured that it may not last our lifetimes (it is in the third picture of the day). A large chunk fell about fifteen years ago. Wall Arch, another arch in the same area, just collapsed last summer.

Today's first photograph shows a small arch in the vicinity of Delicate Arch (a corner of Delicate is visible on the left side). The foreground includes tilted layers of the Entrada where they collapsed into the salt anticline. The La Sal Mountains can be seen in the distance.

The second photo shows my nomination for one of the most dramatic trails in existence, the one that leads to Delicate Arch. This is definitely a case where the end of the trail is not the main attraction; the whole trail is a treat, from one end to the other.

Unfortunately, politics and politicians don't stop politicking, elections or not. Arches, like the Grand Canyon is being threatened by the possibility of gas drilling just outside the park boundaries. The outgoing administration seems to be trying to run a fire sale on leases before they leave office in January. It is especially irritating that the Bureau of Land Management seems to be trying to fly under the public radar in their announcements. More information on the issue (and maps of the proposed leases) can be found here.

Friday, October 17, 2008

The Real Jurassic Parks: Arches National Park

There are many such places. Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, the right place, the one true home, known or unknown, actual or visionary. A houseboat in Kashmir, a view down Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, a gray gothic farmhouse two stories high at the end of a red dog road in the Allegheny Mountains, a cabin on the shore of a blue lake in spruce and fir country, a greasy alley near the Hoboken waterfront, or even, possibly, for those of a less demanding sensibility, the world to be seen from a comfortable apartment high in the tender, velvety smog of Manhattan, Chicago, Paris, Tokyo, Rio or Rome-there's no limit to the human capacity for the homing sentiment. Theologians, sky pilots, astronauts have even felt the appeal of home calling to them from up above, in the cold black outback of interstellar space.

For myself, I'll take Moab, Utah. I don't mean the town itself, of course, but the country which surrounds it--the canyonlands. The slickrock desert. The red dust and the burnt cliffs and the lonely sky--all that which lies beyond the end of the roads."

These are the opening words of one of the most influential books in my life: Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey. I first read it in the last years of my adolescence, just when I was searching for a direction in my life. What could I do for a career that would combine a love of wilderness, the chance to spend time in the outdoors, and teaching about the wild places to those who haven't been there yet? After reading his book, I wanted to be a park ranger in the worst way, although that desire was later tempered by the realization that I would have to be more of a policeman of the wilds, dealing with a recalcitrant bureaucracy, and dealing with all manner of moronic tourists (ok, not all of them...but still...). His book, published in 1968, was a description of a summer spent as a ranger in what was then Arches National Monument. The monument was, at the time, one of the most remote corners of North America, barely accessible by rough dirt tracks, generally unvisited, and one of the most beautiful places in the country. It was a call for protection of the beautiful places, and a warning about the future direction of wilderness management in the Colorado Plateau region.

The book ended up a paradox: it publicized a region of spectacular scenery, which in turn led to a vast increase in visitation which in turn required developments and "improvements" to accommodate the visitors, which in turn threatened to destroy the very wildness that made the region so attractive to start with. Abbey was worried about "industrial tourism", and yet was largely responsible for the fact that it happened in this place that he called the most beautiful on earth.

Well, I never became a ranger, but I was lucky enough to find a career that allowed me to achieve my other goals. As a geology instructor, I have been leading trips into the Plateau region for twenty years, and in a sense, I have become one of the industrial tourists, but usually in the name of education. I want my students to come away with an appreciation of not just the scenery but of the vast history represented by the rocks.

Arches National Park is one of the ultimate expressions of scenery produced by the Entrada Sandstone. More on the park in the next post. For today I provide a picture of one of the more famous sights in the park, Delicate Arch, with the laccolithic La Sal Mountains in the distance. It lies at the end of a stunning 1 1/2 mile hike across the slickrock that ranks with Angels Landing as one of my favorite strolls in North America.

Saturday, October 11, 2008

The Real Jurassic Parks: Kodachrome Basin (and a great resource!)

Back on the (virtual) road with our exploration of the geology of the Colorado Plateau, and the current series on the REAL Jurassic Parks. In our last post we were chasing "Galaxy Quest" rock monsters through Goblin Valley. Today, we are seeing another of the little-known gems of the Plateau country, Kodachrome Basin State Park in southern Utah. Kodachrome is another park that puts the Entrada Sandstone on prominent display along with something like four dozen unusual formations called clastic pipes.

Back on the (virtual) road with our exploration of the geology of the Colorado Plateau, and the current series on the REAL Jurassic Parks. In our last post we were chasing "Galaxy Quest" rock monsters through Goblin Valley. Today, we are seeing another of the little-known gems of the Plateau country, Kodachrome Basin State Park in southern Utah. Kodachrome is another park that puts the Entrada Sandstone on prominent display along with something like four dozen unusual formations called clastic pipes.These enigmatic features jut through the Entrada Sandstone, and being better cemented than the surrounding rock, they tend to stand out as towers tens of feet high (the highest are more than 100 feet). They are mostly composed of breccia and sandstone. Their origin is unclear, although there are plenty of well-considered hypotheses including cold and hot springs, earthquakes, overburden pressure, and UFO's (they always have something to do with weird things out here). I have no particular expertise to judge, but I have to note the presence of several major fault zones in the immediate vicinity, and can easily imagine an origin rooted in liquefaction effects (this statement acknowledges the fact that we can see the things we know about and can miss evidence favoring things we know nothing about...).

Some of the pipes are exposed in their original matrix of Entrada, as can be seen in the second photograph. Notice how the strata form a graben or syncline in the area adjacent to the pipe.

Why the unusual name? Aren't there trademark restrictions or something on such blatant commercialism? Actually, the name was given to the basin in 1949 by the National Geographic Society following an expedition in the region. Yes, an expedition. Even today, the area remains one of the most isolated corners of the lower 48 states. They were using the newfangled color film, and were inspired by the intense coloration of the rock (for those of us too young to remember, there was a time before digital cameras....). The basin became a state park in 1962, and was called Chimney Rocks for fear of trademark infringement or something, but Kodak recognized good PR, and happily let the state keep the name. They have even sponsored park brochures (in color, of course).

If you are leading a field trip through the region, and find nearby Bryce Canyon too crowded and noisy, consider Kodachrome as an overnight stop. There are two nice group campsites, and a good shower facility (we of the long trip persuasion have to remember the basics....). A network of short trails explores the park, and a short drive east reveals the spectacular Grosvenor Arch. A longer gravel road (Cottonwood Canyon Road) travels south along the Cockscomb Monocline, emerging near Page and Glen Canyon Dam. It's a great drive...in dry weather. Don't try it after storms! The Utah State Parks website for Kodachrome can be found at http://stateparks.utah.gov/parks/kodachrome/.

BTW, geology road guides for all state and national parks in Utah can be accessed at http://www.utahgeology.org/uga29Titles.htm. These are PDF's of the first edition of the truly excellent book Geologic Road, Trail, and Lake guides to Utah’s Parks and Monuments, P.B. Anderson and D.A. Sprinkel, editors (Utah Geological Association-29 Second Edition, , 2004, CD-ROM, $14.99. Available at the DNR Map and Bookstore, http://mapstore.utah.gov/ ). The roadguides are a companion to the very comprehensive Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments, also available from the Utah Geological Association.

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

The Real Jurassic Parks: Goblin Valley and the Entrada Sandstone

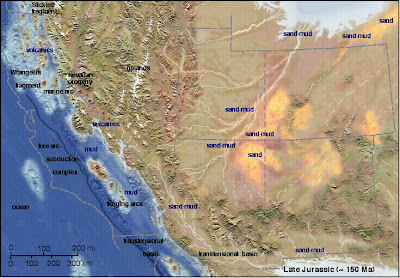

This paleogeographic map is courtesy of Ron Blakey at Northern Arizonal University

Welcome to one of the most unusual (and most isolated) parks in the American Southwest, Goblin Valley State Park. It is located in south-central Utah, miles from anywhere (the relative metropolis of Green River, population 973, is about 50 miles away). It is a fine introduction to the Entrada Sandstone and Summerville Formation, two of the more scenic layers within the San Rafael Group.

In the latest part of the middle Jurassic (around 165 million years ago) huge changes were taking place across the American west. A subduction zone had formed off the coast of California, and compressional forces had caused the faulting and uplift of a range of mountains across Nevada. A shallow sea occasionally extended into the region from the north, leaving vast deposits of mud, silt and sand deposited in tidal flats, while in other areas river floodplains and desert dunes predominated (the region still lay across the subtropical belt, much like the Sahara today). The sediments, which have a distinctive red-brown color, are known today as the Entrada Sandstone.

In other regions, the Entrada is primarily a cross-bedded sandstone that forms distinctive cliffs, but here at Goblin Valley, the formation is more variable, with alternating layers of sand, silt and shale that erode in a differential manner, forming slopes and ledges.

The Goblins are short spires called hoodoos, which resulted from the erosion along joints and fractures in the rocks. If you are a fan of the movie "Galaxy Quest", will immediately recognize the park, and will probably be looking for cute little purple cannabilistic space aliens and immense rock monsters. You will probably be disappointed in your search, but your imagination will probably conjure up even more fantastic creatures as you wander through the goblins.

The park includes a unique campground that is nicely developed with showers and flush toilets but very little shade (there is a nice group campsite too). During the summer we make a point of arriving in the late afternoon when the sun is approaching the western horizon. The views east are expansive, and few parks in the American west offer better star-gazing. The San Rafael Swell, a huge monocline, lies just to the west. The Henry Mountains, one of the last mountain ranges in the United States to be given a name, lie just to the south. Reaching over 11,000 feet, they are a series of laccoliths, a unique type of mushroom-shaped intrusion, almost, but not quite volcanoes (although volcanoes may have once existed above them). The region is also a great place for seeing pronghorn antelope!

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

The Real Jurassic Parks: The San Rafael Group

I've been meaning to return to my continuing narrative on the geology of the Colorado Plateau; I didn't want to strand you all in the early Jurassic, as pretty as the rocks of that time are. The next layers on the plateau are a highly variable series of formations from the middle Jurassic gathered together as the San Rafael Group. A lot of geologic action was taking place throughout the region at the time, with the occasional incursion of shallow seas to the region, continuing desert conditions, rivers and floodplains, and maybe even a local asteroid impact. Some of them are formidable scenery-makers, especially the Entrada Sandstone, the subject of the next few posts.

I've been meaning to return to my continuing narrative on the geology of the Colorado Plateau; I didn't want to strand you all in the early Jurassic, as pretty as the rocks of that time are. The next layers on the plateau are a highly variable series of formations from the middle Jurassic gathered together as the San Rafael Group. A lot of geologic action was taking place throughout the region at the time, with the occasional incursion of shallow seas to the region, continuing desert conditions, rivers and floodplains, and maybe even a local asteroid impact. Some of them are formidable scenery-makers, especially the Entrada Sandstone, the subject of the next few posts.Today's photo is an early morning shot from the campground at Goblin Valley State Park in south-central Utah, showing a unique outcrop pattern of the Entrada. It's a teaser, though. More later!

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Time Beyond Imagining

Still decompressing after a "long" trip of two weeks through geologic time on the Colorado Plateau. It is always difficult to comprehend the contrast between the hours and days of one's human existence with the millions and billions of years that characterize the geologic history of our planet and Universe. I expect to follow this theme in my blogs for a few days as I sift through the pictures of our journey.

Still decompressing after a "long" trip of two weeks through geologic time on the Colorado Plateau. It is always difficult to comprehend the contrast between the hours and days of one's human existence with the millions and billions of years that characterize the geologic history of our planet and Universe. I expect to follow this theme in my blogs for a few days as I sift through the pictures of our journey.The unusual view above comes courtesy of astronomical lunar cycles and Landscape Arch in Arches National Park. The arch has an opening nearly as long as a football field, and is only 6 feet or so across at the thinnest point. It is rather a wonder that the span still stands, and the future prognosis of the arch is probably measureable in human, not geologic, terms. A large chunk fell from the span around 1991.

The arches in the park are formed in the Slickrock Member of the Jurassic Entrada Sandstone. The unit has been pushed upwards by bodies of mobile salt from the late Paleozoic Paradox Basin. The upward pressure in the salt anticline has fractured and jointed the sandstone into a series of "fins", long narrow walls of rock. The base of the fins lie in the Dewey Bridge member of the Entrada (or Carmel), which is easily eroded, allowing a small window to form at the base of the fin. Chunks of rock fall from the window, until an arch develops. There are hundreds in the park.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)