When traveling with 35 students, one must plan each day carefully. You have to be cognizant that everyone does not operate on the same bladder timing plan, that people on the trip have different metabolisms, that every stop has the potential of becoming a long delay. One tries at all times to keep to a carefully planned schedule with highly calibrated rest stops at appropriate intervals, and academic stops are structured so as to enhance the learning experience in line with the course learning objectives and previous successful academic outcomes.

And sometimes you just have to say screw it all and try something totally different.

We were well into our journey into the

Abandoned Lands, an exploration of the Colorado Plateau, and we had crossed the Utah state line and were driving north on Highway 191 towards Moab and Arches National Park. We were leaving the lands of the Ancestral Pueblo people, and were coming into a region with a general paucity of obvious archaeological remains. It is a land of barren rock where water is scarce and survival difficult without the niceties of modern technology. It is the realm of the geologist.

The region between Moab and Monticello is a complex mix of anticlines, faults, and laccolithic intrusions. The combination of these structures has led to the formation of a variety of ore bodies, and the history of this landscape is tied mostly to the search for those ores, by ancient peoples as well as modern prospectors.

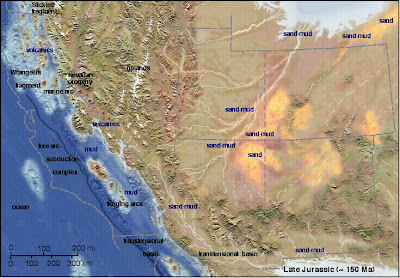

As we drove north we passed Church Rock, an outlier of Jurassic Entrada Sandstone. The Entrada accumulated in coastal sand dunes and muddy estuaries along a western sea. Conditions were quite arid at the time, as it was situated in the subtropics, much like the Sahara Desert today.

The plan was to make a sensible stop at a roadside rest area and continue on to our camp for the night at Arches National Park. But I was looking at the highway maps and geology road guides, and I found myself asking "why don't any of these guides say anything about Highway 113 and the uranium mines out in the Lisbon Valley Anticline?" Yes, sometimes we think that way. So, I got on radio and said we were turning onto Highway 113 to simply see what was there. It was serendipity...

I turned onto this road, which really did have kind of an abandoned look to it. As mentioned previously, I had no guides, and I had never been on the highway before, but I knew that somewhere in the ridges ahead was the fabled and deadly Mi Vida Mine, discovered by Charlie Steen in 1952.

Charlie Steen looms large in the legends of the "uranium frenzy" that gripped the Colorado-Utah borderlands in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Uranium and vanadium had been mined in the region intermittently during the early part of the century, but production was limited. It was the invention of the atomic bomb, the Cold War, along with a recession following World War II that left thousands of soldiers in the unemployment lines that led to an unprecedented migration into this barren region. It was also the first government-sponsored mining boom, as the bureaucrats promised to maintain a minimum price for uranium for at least a decade.

Charlie missed out on the draft for medical reasons, but went to work in the oil industry. By behaving just like a geologist, he got himself fired for insubordination and could not find employment anywhere in Texas. Hearing of the uranium rush, he piled his young wife and four very young sons into a surplus jeep, mortgaged his mother's home for $1,000 and headed north into the Utah Canyon Country. As a geologist, he had some ideas about where the yellow carnotite uranium ores might be found, and his ideas were viewed with amusement by his colleagues. But he sunk the last of his dollars into a drilling rig and set up on the limb of the Lisbon Valley Anticline. For months his family subsisted on poached venison stew and cereal while he drilled the 200 foot hole.

And the drill bit broke off...

He was beat. There was nothing in the hole but some kind of black coal-like material, not the bright yellow carnotite that everyone was looking for. He had samples of the black stuff in the back of the jeep when he rode into Moab for the maybe the last time.

Did I mention that Steen couldn't even afford a Geiger Counter? According to the stories I've read, he either grabbed someone with a counter to test his samples, or someone walked past his jeep with a Geiger Counter that happened to be switched on, but in any case the counter went crazy. The black stuff turned out to be pitchblende, the richest ore yet discovered on the Colorado Plateau. The layer was 70 feet thick. In a short moment, Steen went from the poor house to Boardwalk and Park Place. He named the mine the Mi Vida ("My Life").

By most accounts, Charlie Steen was generous with his new-found riches, donating to many charitable causes in the Moab area, and he apparently threw great parties. When he got frustrated with haulage costs to the government milling facilities, he built his own mill in Moab right next to the Colorado River. I suppose that it is ironic that the many millions of dollars worth of uranium that the mill produced is kind of balanced against the fact that uranium has been leaching into the Colorado River ever since, and that $300 million is being spent to haul the waste dump to a site near Cisco, one of the places that Charlie had lived in poverty.

|

| Does anyone think that this rock is an alien monument to Jabba the Hut? |

In any case, uranium transformed the Canyonlands country. Miners forced access roads into the most inaccessible terrain imaginable in search of riches. The small towns grew rapidly and sometimes painfully. But perhaps the most terrible heritage of the entire episode is that the miners were never told of the horrific dangers of mining uranium from underground mines. Radon gas was a byproduct of the radioactive decay of the uranium, and some of the unventilated mines had gas levels thousands of times the currently accepted safe level. It was hard to accept the danger from an invisible monster that took years to do its work.

Miners worked for a decade or more in the mines, but eventually many of them developed lung cancer and other diseases, and they started dying. Their families suffered too. The dangers came from wives washing coveralls covered with carnotite dust, children playing on mine dumps, and swimming in uranium-saturated waters at the mine sites. The sadness came in the arbitrary nature of the fatalities. Surprisingly healthy miners watched their children die in some instances.

We headed up the road onto the flank of the Lisbon Valley Anticline. We passed a rock that I knew must have had a name, but I had never run across it before (I found out this week that it is called Big Indian Rock).

Without maps or notes, we passed up the Mi Vida (it was tucked away in a side canyon), but saw plenty of evidence of other mining ventures. The anticline was the result of salt bodies rising and piercing the overlying rocks (the salt formed in estuaries and bays that came to be cut off from the western ocean in Pennsylvanian time). Thirty million years ago, the intrusions of the magma that formed the large laccolithic intrusions of the La Sal Mountains and Abajo Mountains provided the hydrothermal fluids that formed ore bodies along fault systems in the anticline folds. The ores included the uranium, but copper was also a major component.

We pulled over at a large open pit operation to have a look. It looked abandoned, but we stayed along the highway just the same. It turned out to be a copper mine, and bits and pieces of azurite and malachite littered the dirt along the road. Of course serendipity cuts both ways. The mine was not abandoned at all, and we were chased off by an irate security guard.

It was a fascinating look at a sad heritage. We made our way back to Highway 191 and soon arrived at Arches National Park, one of the most stunning landscapes on the planet. Our adventures will continue in a future post.

POSTSCRIPT: Check out Andrew Alden's excellent new post on uranium geology for some details on the mineralization process:

http://geology.about.com/od/mineral_resources/a/uraniumnuts.htm