|

| Makauwahi Cave and Sinkhole as it is today |

I learned to my great surprise that Hawai'i has a few (very few, really) limestone caves.

In part one I talked about the odd origin of Makauwahi Cave on the island of Kauai. In that post we learned that the limestone formed from limestone sand dunes that formed near Poipo Beach. The sand was lithified (glued together), and fresh water dissolved the limestone, forming the cavern, which has around 500 feet of passageways. At the end of the post I alluded to the fact that the cave was witness to three catastrophes that I'll look at today. On reflection, though, I think it's fair to say there were actually four catastrophes, one local, and the others island-wide.

How did these catastrophes transpire? The rock formed around 400,000 years ago, and the passageways grew larger over time. By 7,000 years ago, wave action broke through and for perhaps a few centuries the cave was both a limestone cavern and a sea cave. Marine fossils formed a layer on the cave floor. But the waves may have contributed to the first catastrophe, because a short time later the roof of the cavern collapsed and formed a sinkhole. This is the bowl-shaped pit that is visible in the photo and painting above. The debris plugged the access to the sea, and the cavern and sinkhole filled with fresh water.

But is the collapse of a sinkhole a catastrophe? I guess it depends on your perspective. Some of the rarest of species on an island system with thousands of rare species would be those lifeforms adapted to living in total darkness. There are three blind species living in the darkness of Makauwahi Cave today, an amphipod, an isopod, and a blind spider (below) that feeds on the other two. These creatures have one of the most restricted environments possible on the islands, and the collapse severely restricted their living space.

|

Blind cave wolf spider (descended from a surface-dwelling big-eyed spider, so it's sometimes called the no-eyed big-eyed Spider). Photo by Michelle Clark, USFWS.

|

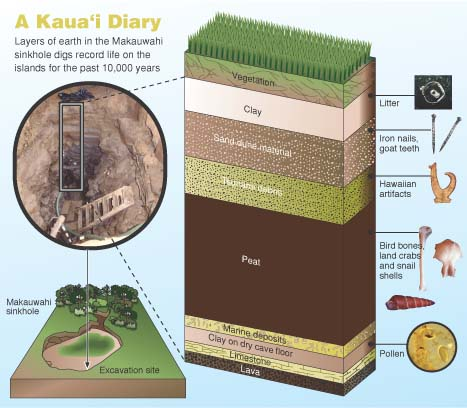

The real "catastrophe" is what followed the formation of the pond in the bottom of the sinkhole. Animals found their way into the pit, but no way out. The pit became a death trap. Over the next few thousand years huge numbers of fossils, both animals and plants, accumulated in the sinkhole. The organic rich mud (peat) grew to be one of the thickest layers within the pit (see below). Excavations since the 1990s have revealed thousands of specimens that have revealed more about the pre-human environment on Kauai than any other site on the island.

The primeval world of Kauai and the other Hawaiian Islands was unique. The islands are so isolated that no reptiles, amphibians, or mammals ever reached the islands (aside from seals and bats). The only vertebrate creatures that found their way to the islands were the birds. As a consequence, the environmental niches in the island ecosystem were filled by avian species, and over time they adapted and evolved to fully utilize the resources available to them. Species of hawk and owl filled the role of predator, especially of smaller birds. Ducks and geese grew to immense size and lost the ability to fly, given the lack of larger predators (see below). They took over the niche of plant-eaters and grazers. The honeycreepers were the most astounding example of evolutionary adaptation. From a single Asian finch-like ancestor, more than 50 distinct species evolved, filling the niches occupied elsewhere by parrots, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, and insectivores. Sadly, most of them are extinct and most of the survivors are critically endangered.

How unique is the Makauwahi fossil record? Of 107 bird species known to have been endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, nearly half (50 species) have been found in and near the sinkhole. Several species were found here and nowhere else on the islands.

Some of the unique birds include a flightless goose, a turtle-jawed moa-nalo bird, a long-legged owl that probably fed on other birds, and a little duck with tiny eyes, a flat skull and tiny wings that probably fed on forest insects at night. Several of the birds like the hawk and Laysan duck no longer survive on Kauai, but are still found on other islands.

Another catastrophe happened about 300-400 years ago. Excavators digging in the sinkhole found their way barred by a layer of boulders weighing as much as 200 pounds. These rocks were a mixture of basalt, lithified dune sands, and coral. The only process that could pile such debris in a sinkhole like this would be a huge tsunami. There must have been a village nearby because the deposit also contains some human artifacts like pieces of canoes, ropes, and ornamental objects. These rocks and other objects were carried over a ridge 27 feet above sea level, meaning the wave must have been much taller.

Humans in Hawai'i have always had to deal with the threat of tsunamis. The location of the islands near the center of the Pacific Ocean means that they can be hit by waves from all directions, generated by earthquakes in places as far-flung as Japan, Alaska, Washington, and Peru-Chile. Strangely, the largest tsunamis of all have been generated by the Hawaiian Islands themselves. Gigantic mega-slides from the flanks of the islands flowing onto the adjacent deep ocean floor have generated waves in excess of a thousand feet high! Thankfully, no such waves have occurred in historic time.

The biggest change at Makauwahi Cave was that the pond had been filled in and it was no longer a fossil trap. But the third and fourth catastrophes become visible in the sediment record of the cave: the arrival of human beings on the islands.

The landscape surrounding the sinkhole (above) is far, far different than the one that existed prior to a thousand years ago when the first Polynesians reached Kauai, the third catastrophe. Hardly any native vegetation remains. Humans have been successful at geo-engineering their environments to provide the food and resources they need to survive and flourish. The colonizers brought taro plants, coconuts, kukui nuts, and gourds, as well as dogs, pigs, chickens, and whether on purpose or not, the Pacific rat. These invasive plants and animals overwhelmed the native flora and fauna, driving many species to extinction, or to much more limited ranges.

The effect on the birds was truly catastrophic. Evolving in isolation, they had no defense against the mammal invaders. The flightless birds quickly disappeared, and many other species suffered huge declines (above).

Still, from a human point of view, a certain equilibrium had been achieved, even if the native species went into a steep decline. Humans had been expanding across the Pacific islands for centuries, and knew what resources they would need to bring with them when they found new islands to colonize. They also had a social structure that was rather efficient and strict (however unjust to our present sensibilities) that allowed the native Hawaiians to thrive in their new environment, largely operating within the carrying capacity of the lands they were occupying.

The fourth catastrophe began unfolding in 1778 when Captain James Cook and his crew arrived. The full extent of this event is also revealed in the sediments of Makauwahi Cave, but we'll take that up in part 3.

The authoritative source of information on Makauwahi Cave is the book Back to the Future in the Caves of Kaua`i: A Scientist’s Adventures in the Dark; David A. Burney, Yale University Press, 2010.