Showing posts with label northern California. Show all posts

Showing posts with label northern California. Show all posts

Friday, July 7, 2017

Just How Big is Mt. Shasta in Northern California? Getting a sense of scale...

Mt. Shasta is a big mountain. It becomes visible from upwards of a hundred miles away. Topping out at 14,180 feet (4,322 m), it has the greatest volume of any Cascades stratovolcano at around a hundred cubic miles of lava flows and ash (the less visible shield volcanoes like Medicine Lake Highland are larger however). Driving north on Interstate 5, the mountain edifice takes on the very definition of "looming".

On our recent journey through the Pacific Northwest, Mt. Shasta was our first lecture stop. We drove up the flank of the mountain to an elevation of 7,000 feet or so at Bunny Flat, where we were stopped by snowdrifts...in late June. It's been a wet year!

It's hard to get a true sense of scale sometimes when observing really big mountains, but my camera has a pretty dandy zoom lens, so I had a bit of fun with it. In the picture above, note how the center of the picture is completely snowbound, except for three rocks near the top of the ice slope. I zeroed in on it.

In the photo above, we can see those three large rocks a bit more clearly. Keep in mind that we are already 7,000 feet up the mountain. There is more than a mile of mountain above us.

Zooming in once more, we can see that there is more than just three big rocks on the slope. It's hard to get a sense of how big they might be, except that at this scale we can see some more very small black dots scattered about the slope. What could they be?

At the highest zoom (60x), the small dots resolve into human beings. It was a hot day in the valley, so a lot of people were up on the slopes of Mt. Shasta keeping cool. And yes, Shasta is a very big mountain.

Friday, December 9, 2016

Magnitude 6.5 Earthquake off Northern California (as recorded at MJC)

A large earthquake has shaken the ocean floor off the coast of Northern California. It took place about 100 miles west of Cape Mendocino (below) and the town of Ferndale. The 6.5 magnitude event took place on the oceanward extension of the San Andreas fault roughly halfway between the Gorda Ridge and the south end of the Cascadia Subduction Zone. The first motion diagram for the event is consistent with a right lateral strike-slip fault. The lateral motion of the shaking minimized the chances of producing a tsunami, and none was reported. The quake was felt over a large part of the North Coast, but I expect there was little damage. A hundred miles is a good distance to be away from an epicenter.

We got a good record of the event on our instructional seismometer at Modesto Junior College. I would have posted earlier, but found that although the event was recorded, the monitor had fizzled out and had to be replaced so I could see what I was doing to preserve the seismograph of the event.

Earthquakes are not unusual in this area, and indeed there have been some destructive events over the years, including a 7.2 magnitude event in 1992 that caused some serious damage. It is a complex region, with a divergent plate boundary offshore of a subduction zone, and the transform boundary of the San Andreas fault.

All in all, the best kind of earthquake: big and noisy, but far enough away that no one gets hurt. For more details, check out the details at the USGS: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us20007z6r#executive

|

| Cape Mendocino, the closest land feature to the 6.5 magnitude quake on Thursday. |

|

| Source: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us20007z6r#map |

All in all, the best kind of earthquake: big and noisy, but far enough away that no one gets hurt. For more details, check out the details at the USGS: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us20007z6r#executive

Sunday, August 2, 2015

Vagabonding on Dangerous Ground: "This Dismal Forest Prison" and Other Problems Exploring the Northwest

One of the things that really struck me as we went vagabonding up the Cascadia Subduction Zone last month was how rugged the landscape was. There is a topographic consequence to traveling or living onshore of a convergent boundary. In the long term, the land is pushed upwards into mountains, mountains that in many cases slope directly into the sea. Add to this the orographic effect, which dumps multitudes of rainfall in this northern latitude, and you end up with nearly impassable terrain.

On our trip, we occasionally felt a tiny bit of impatience when the road narrowed and went from four lanes to two. It slowed us on our journey through northern California and southern Oregon. It meant that the coastal route cost us a good thirty or forty minutes over what the trip would have been had we traveled on Interstate 5 farther inland. Thirty or forty minutes! A whole five hours or so to cover the 200 miles from Crescent City to Florence! But it took only a few moments of consideration to realize what an easy time of it that we have getting from one place to another in this landscape, this incredibly rugged and even dangerous landscape.

|

| Samuel Boardman State Park on the south Oregon Coast |

One of the books we picked up on the journey was called "Two Peoples, One Place " by Raphael and House. It is a history of Humboldt County, and it is a bit unusual in that includes a great deal of information about people other than the Europeans who settled the region in relatively recent times. I haven't read all of it yet, but I was struck by one section, an account of the overland journey that resulted in the discovery of Humboldt Bay in 1850.

It was a miserable journey, by all accounts. The party of eight men took ten days of food supplies for an expedition that lasted around two months. The Gregg Party made their way from the Trinity River to the coast around Patrick's Point, then south through the Humboldt Bay and then up the Eel River. The party split up, with some of them attempting a more coastal route to San Francisco, but ending up in the Sacramento Valley. Gregg himself, their leader, died under somewhat disputed circumstances. The others followed the Eel River, during which they had a tough encounter with eight (8!) grizzly bears. They limped their way south to Sonoma.

The surviving accounts suggest that Gregg was not well-liked by his crew. He was constantly slowing the expedition by taking scientific readings (you know how those scientists are!). Sadly his notes and records were lost (or discarded unceremoniously after his death). How is this for a description of an argument that took place among the crew?

His cup of wrath was now filled to the brim; but he remained silent until the opposite shore was gained, when he opened upon us a perfect battery of the most withering and violent abuse. Several times during the ebullition of the old man's passion he indulged in such insulting language and comparisons, that some of the party, at best not any too amiable in their disposition, came very nearly inflicting upon him summary punishment by consigning him, instruments and all, to this beautiful river.This is, by the way, how the Mad River got its name...

Though they were impressed by the size of the Redwood Trees, they referred to them as a "dismal forest prison". They described the near impossibility of moving their livestock and supplies through the forest floor, as it was covered with multitudes of fallen trees. They were lucky to make two miles a day. In the end they survived mostly by the generosity of the local Native American people who lived in the region. They gave the Eel River its name because of the lampreys they traded for to eat (sounds delicious).

|

| Arch Rock in Samuel Boardman State Park |

|

| Samuel Boardman State Park |

But in the present day, it is possible drive the entire coast from Eureka to central Oregon in a long afternoon. And in the absence of the dangers of scurvy, grizzly bears, or starvation, the traveler can sit back and appreciate the incredible beauty of the region. One feels compelled to slow down and enjoy the scenery. Oregon has established a string of state parks along the rugged southern coast of the state, and each one of them is worth a stop.

|

| Pistol River State Park in southern Oregon |

|

| Cape Blanco State Park is only about seven miles short of the being the westernmost point of the lower 48 states. Cape Alava in Washington is the far west point. |

The bridge over the Siuslaw River at Florence Oregon is one of the most beautiful. Tell me this doesn't look just a little like a cathedral...

When we reached Coos Bay and Florence, the nature of the coastline changed radically. In the next post, we'll be talking about sand. Lots and lots of sand.

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

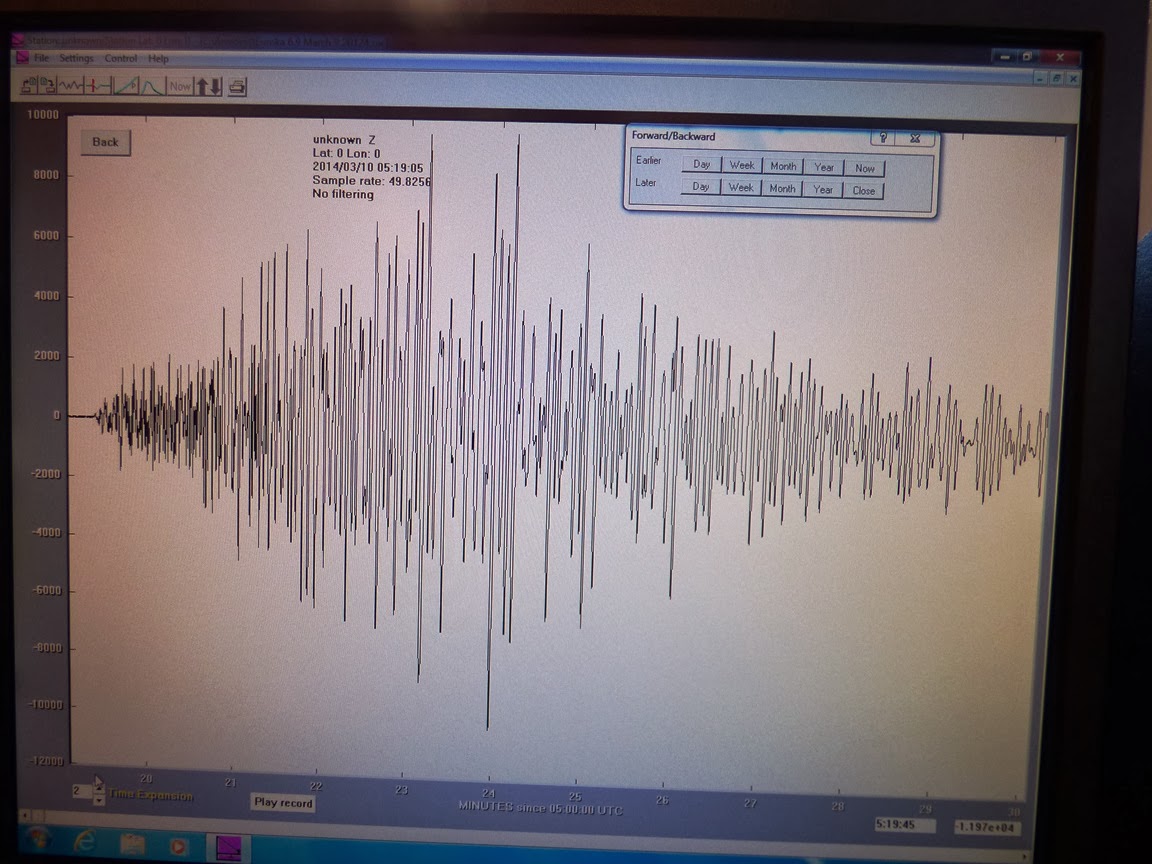

California's 6.9 Magnitude as Recorded at Modesto Junior College

Here is California's 6.9 magnitude earthquake from last Sunday as recorded on our rather simple seismometer situated on the West Campus of Modesto Junior College. The unit is up on the third floor of the new Science Community Center, which is not ideal from a recording standpoint (the building is subject to all kinds of vibrations), but it's wonderful as an educational tool. We have one of the monitors up against a window where students can check for earthquake activity (and of course jump up and down to make their own earthquakes). The activity across the bottom of the record is the vibration of students walking by on Monday morning. This is the first major seismic event that we've recorded since installing the unit.

The horizontal lines on the monitor represent one hour increments, so the whole screen covers about 24 hours. The quake happened at 10:18 PM local time, and the shaking lasted for a good fifteen minutes. This doesn't mean that people were being shaken the whole time, because the actual humanly perceived shaking lasted only about 15 seconds. Instead, the ground continued to reverberate more slowly, so the movement was imperceptible. The waves would have continued all over the world and through the planet as well. They would have been detectable on a seismometer in India or Africa.

Here is the isolated and expanded version of the event. It covers about eleven minutes of the shaking:

Sunday, March 9, 2014

Magnitude 6.9 Earthquake Offshore of Northern California

A moderately large earthquake has been recorded offshore of Northern California, measuring 6.9 on the magnitude scale. It took place about fifty miles offshore of Ferndale, Eureka, and Arcata at 10:18 PM local time. It was apparently felt all over northern California, as far south as the Bay Area. There haven't been any reports of damage or injuries.

The quake took place in a complicated region where the San Andreas fault system intersects with the Cascadia subduction zone. It is close to the Mendocino Triple Junction where the Pacific, North American, and Gorda Plates are in contact with each other. Moderate quakes are not at all unusual in the region, with quakes measuring between 6.4 and 7.2 in 1923, 1932, 1954, 1980, 1992, and 2010. The Cascadia subduction zone generated a quake of around magnitude 9 in 1700, although it was farther north in Washington and Oregon.

A tsunami warning was not issued, presumably because the ocean floor was not lifted enough to cause one. Tsunamis are most commonly produced during compressional earthquakes in subduction zones, events that cause hundreds or thousands of square miles of seafloor to suddenly rise or subside. A quake the size of this one was either on a predominately strike-slip fault, or just didn't disrupt enough of the seafloor a sufficient distance.

As I write this, there have been half a dozen aftershocks recorded, mostly around magnitude 3, with one magnitude 4.6 event. There were also a few magnitude 3 events that could be considered foreshocks. Latest information from the U.S. Geological Survey can be found here: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/nc72182046#summary, although I like the SCEC earthquake maps at http://www.data.scec.org/recenteqs/Maps/125-41.html as well.

I'll post updates if I get more information. I can hardly wait to see if the new seismograph at school was working this weekend!

UPDATE: A good synopsis of the geological circumstances of the quake has been posted at http://seismo.berkeley.edu/blog/seismoblog.php/2014/03/10/the-strongest-california-earthquake-in

The quake took place in a complicated region where the San Andreas fault system intersects with the Cascadia subduction zone. It is close to the Mendocino Triple Junction where the Pacific, North American, and Gorda Plates are in contact with each other. Moderate quakes are not at all unusual in the region, with quakes measuring between 6.4 and 7.2 in 1923, 1932, 1954, 1980, 1992, and 2010. The Cascadia subduction zone generated a quake of around magnitude 9 in 1700, although it was farther north in Washington and Oregon.

A tsunami warning was not issued, presumably because the ocean floor was not lifted enough to cause one. Tsunamis are most commonly produced during compressional earthquakes in subduction zones, events that cause hundreds or thousands of square miles of seafloor to suddenly rise or subside. A quake the size of this one was either on a predominately strike-slip fault, or just didn't disrupt enough of the seafloor a sufficient distance.

As I write this, there have been half a dozen aftershocks recorded, mostly around magnitude 3, with one magnitude 4.6 event. There were also a few magnitude 3 events that could be considered foreshocks. Latest information from the U.S. Geological Survey can be found here: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/nc72182046#summary, although I like the SCEC earthquake maps at http://www.data.scec.org/recenteqs/Maps/125-41.html as well.

I'll post updates if I get more information. I can hardly wait to see if the new seismograph at school was working this weekend!

UPDATE: A good synopsis of the geological circumstances of the quake has been posted at http://seismo.berkeley.edu/blog/seismoblog.php/2014/03/10/the-strongest-california-earthquake-in

Thursday, January 2, 2014

The Stacks are Odded Against Us! Subduction's Gift in Southern Oregon and Northern California

|

| Sea stacks on Highway 1 near Elk, in Northern California |

|

| Sea stacks at Point Orford in Oregon |

Subduction zones produce some of the worst of geologic disasters, including massive earthquakes and devastating tsunamis. But the deformation of the Earth's crust also causes the formation of mountains and rugged coast lines that make some of the world's most beautiful scenery. And that is where today's post originates. I had the privilege of spending a few days making my way south along Oregon 101 and Highway 1 in Northern California on my way home from Christmas visits, and we saw a stunning variety of shoreline features including the sea stacks that I am emphasizing today.

|

| Sea stacks near Brookings, Oregon, I think. Anyone recognize them? |

|

| Restless seas in the morning at Fort Bragg in Northern California |

|

| At the mouth of the Navarro River just south of Mendocino in Northern California |

|

| Sea arch in a stack at Navarro Beach in Northern California near Mendocino. |

|

| Sea stacks at Navarro Beach on the Northern California coast. |

Labels:

Brookings Oregon,

Elk,

Fort Bragg,

Navarro River,

northern California,

Oregon,

Point Orford,

sea stack

Monday, February 13, 2012

Magnitude 5.6 Earthquake in Northern California

There was a magnitude 5.6 earthquake in Northern California at 1:07 PM, at a depth of 20 miles. It took place in a lightly populated area, but I assume it was felt in Eureka and other north coast towns. It occurred on land between Eureka and Crescent City, roughly between Redwood Creek and the Klamath River, very close to the Hoopa Reservation.

As can be seen in the map above, earthquakes are not unusual in this area. It lies north of the triple junction where three tectonic plates come together (the Gorda, Pacific and North American). A subduction zone is forcing the Gorda Plate beneath the North American continent, and earthquakes are to be expected. There have been a series of magnitude 7 quakes in the region over the years, including the Petrolia earthquake of 1992. Ultimately the descending plate starts to melt, producing the magmas responsible for California volcanoes like Lassen Peak and Mt. Shasta.

As can be seen from the seismicity map of California above, there have been plenty of earthquakes within the last week, but there is nothing happening that is out of the ordinary. California averages several hundred earthquakes a week, although most are not felt.

Get the official details at this site: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqsus/Quakes/nc71734741.php#details

Keep track of all the quakes in California here:

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqscanv/

As can be seen in the map above, earthquakes are not unusual in this area. It lies north of the triple junction where three tectonic plates come together (the Gorda, Pacific and North American). A subduction zone is forcing the Gorda Plate beneath the North American continent, and earthquakes are to be expected. There have been a series of magnitude 7 quakes in the region over the years, including the Petrolia earthquake of 1992. Ultimately the descending plate starts to melt, producing the magmas responsible for California volcanoes like Lassen Peak and Mt. Shasta.

As can be seen from the seismicity map of California above, there have been plenty of earthquakes within the last week, but there is nothing happening that is out of the ordinary. California averages several hundred earthquakes a week, although most are not felt.

Get the official details at this site: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqsus/Quakes/nc71734741.php#details

Keep track of all the quakes in California here:

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqscanv/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)