This is the day after the 32rd anniversary of the Loma Prieta earthquake that caused so much damage in the San Francisco Bay-Santa Cruz region, and given that many people in northern California weren't even born by then, and others have moved in, it helps to be reminded that earthquakes are a fact of life in our fair state (and our state is quite fair because of the long-term activity of earthquakes: it's how our mountains formed). There are some assumptions people sometimes make about California and earthquakes, and it seemed to be a good time to dust off some of these old ideas (this is an abridged and updated version of an

article I wrote in 2012)...

It starts with a modest little quiz....

True or False?

- California is going to fall into the Pacific Ocean

- The San Andreas fault causes all California earthquakes

- California has more earthquakes and bigger earthquakes than anywhere else

- The ground opens up and swallows people during earthquakes

- Psychics and animals predict earthquakes

- We in California are waiting for the "BIG ONE"

|

| Comic art courtesy of Zeo |

California is going to fall into the sea: true or false?

This is one of those persistent statements about California earthquakes that everyone "knows", even if they live in New Jersey. Many people would say:

false.

Here's the correct answer:

True!

In fact, not only is it

going to happen, it

already has.

Check out the NASA photo above. When we speak of California, we often forget that most people are only thinking of one part of California:

Alta California (upper California). The image above reminds us that Baja ("Lower") California is also part of our geography. And Baja has already "fallen" into the Pacific Ocean, in a reasonable interpretation of the statement. Baja was once connected to the Mexican mainland, and has been a peninsula for only the last four million years or so. It is the beginning of a massive rift that will ultimately tear Alta California apart, and send it traveling northwest at all of two inches a year. The two inches per year will actually be taken up by large earthquakes shifting the landscape 10-15 feet every century or so.

In 20 million years, the Dodgers and Giants will again be crosstown rivals (yes, I stole this joke from the DVD "Planet Earth"). In 70 million years, California may slam into the south margin of Alaska, pushing up another high mountain range.

Want to see how this happened? Tanya Atwater of UCSB, the plate tectonics pioneer who figured out the origin of the San Andreas fault, has a series of

excellent animations available for download at this site. If you have a fast connection,

try this one (50 mb).

If you have a slower connection,

this animation is 20 mb. Both animations show the complex interactions of the continental margin, with some parts being rotated, and others moving northwest along the San Andreas. And Baja California opening up to form a new seaway, the Gulf of California.

So indeed, it could be a good idea to buy up some property in the western Mojave Desert to be ready for your oceanfront views...in ten million years...if you want to wait that long.

What? You thought the question was about California falling into the sea during one earthquake? Really? Like the movie "2012" or "San Andreas"? Not gonna happen. That's tabloid stuff. Aliens kidnapped me last week too.

|

| Art by Zeo |

By the way, please don't think that the comic art above is belittling the loss of life and property in horrible events like that which struck Japan in 2011. It is actually a critique of the way that news is reported in American media, especially cable news (I'm talking about you, CNN and FOX), and local news outlets.

Question #2 on our short quiz is:

All California earthquakes happen on the San Andreas fault - True or False?

A crowd at a recent lecture I gave, California residents all, were up to date

on this one. Not a single audience member said "true", and they were

right. On the other hand, lots of people don't live in California, and

they might not be quite as knowledgeable about all of California's

faults (double entendre intended). So a few illustrations may be

helpful. First of all, where do the earthquakes in California happen?

See the map below...

A

quick look at the seismicity between 1970 and 2003 shows that

earthquakes occur over much of California, and that the San Andreas

fault is not even one of the most active. Long sections show little or

no activity, meaning that stress is building up, leading to powerful

quakes in the future.

But

what about the biggest quakes? A map that concentrates only on larger

quakes, magnitude 5 and above, shows that large damaging quakes also

happen on faults other than the San Andreas (see the map below). Of

California's three biggest historical quakes, only two were on the San

Andreas. The 1872 Lone Pine quake resulted from movement on the Owens

Valley fault east of the Sierra Nevada.

The good news for those of us who live in the flat,

dusty, boring Central Valley is to note how few earthquakes, big or

little, ever happen near us. Until a

quake in the eastern Sierra Nevada a few months ago, I hadn't actually felt an earthquake here

since the early 1990s, although most of my students felt one during a

class break in 2007 (on a day they were taking a test on earthquakes of all things).

Question three

: California has the biggest and the mostest earthquakes in the world. True or False?

I know that "mostest" is not really a word, but it somehow seems to fit well in the question of the day (a little like Stephen Colbert's 'truthiness'). So, what is the answer? My California audience is usually a little divided on this one, but mostly fall into the "false" camp.

So let's check on some data. If you look at the maps above, you can see that California certainly has a great many earthquakes, perhaps 10,000-15,000 year, and some of them are rather considerable.

There have been three earthquakes in the last 170 years that are thought to have approached magnitude 8 in size: 1857 at Fort Tejon, 1872 at Lone Pine, and 1906 in San Francisco.

|

| San Francisco earthquake of 1906 |

There have been about two dozen magnitude 7 quakes in the same time period, including the Ridgecrest quake in 2019 (7.1), the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah quake in Baja (7.2), the 1999 Hector quake (7.1), and the 1992 Landers quake (7.3).

|

| Fault scarp from 1992 Landers earthquake. Photo by Garry Hayes |

There have been at least 50 quakes greater than magnitude 6.5, meaning that a potentially damaging quake occurs somewhere in California roughly every two or three years. The 1989 Loma Prieta quake and 1994 Northridge quakes caused damage measured in the tens of billions of dollars, and killed dozens of people.

Those are a lot of earthquakes. So let's take the "biggest" issue first. The quake in Japan that destroyed the nuclear power plant and produced the Pacific-wide tsunami was magnitude 9.0. The quake in Sumatra in 2004 that produced the horrific tsunami in the Indian Ocean was magnitude 9.1. So, California doesn't have the biggest earthquakes. Not even close (but check for the wild card issue below, however).

There is a great deal of confusion about the nature of the magnitude scale for measuring earthquakes. It is not a 1-10 scale, for instance, even though literally all recorded earthquakes fall within that range. It is open-ended, and quakes of greater than magnitude 10 are technically possible, but not likely from terrestrial origin. It would take the impact of an asteroid miles across to cause a quake larger than about 9.5 on the magnitude scale.

The biggest confusion concerns the relative size of quakes. Magnitude is a measure of the

energy released when an earthquake strikes. A magnitude 9 quake is not just a little bit bigger than a magnitude 8. It is exponentially larger, by a factor of 32. To put it a different way,

a magnitude 9 quake releases an amount of energy that is equivalent to 32 magnitude 8 earthquakes!

It gets worse: Since a 9 is 32 times more than an 8, and an 8 is 32 times bigger than a 7, a magnitude 9 quake is more than

1000 times larger than a 7 (32x32).

A magnitude 9 quake is the energy equivalent of more than 1,000 magnitude 7 earthquakes...

Put another way:

the Japan 9.0 quake released more energy than all of California's historical earthquakes combined.

The story is pretty much the same with the total number of earthquakes. California has a great many smaller quakes, but just about any subduction zone around the world has more. Even in the United States, Alaska has more earthquakes than California (as well as the second-largest earthquake ever recorded in the world, the 9.3 magnitude Good Friday quake of 1964).

So why does California get this reputation of having an inordinate number of earthquakes? I feel compelled to blame the way news is reported in this country. Cable and local news coverage of earthquakes is atrocious for the most part, with badly misinformed reporters and news-readers (I don't consider them to be news anchors or journalists anymore). There is a tendency to display blood and gore over actual conditions on the ground. The media will spend weeks talking about an earthquake in Los Angeles or San Francisco that kills a few people and practically ignore monumental tragedies in Pakistan or Iran where tens of thousands of people have died.

As mentioned above, there is one wild card in the possibility of large earthquakes hitting California. The state does in fact have a subduction zone that is active north of Fortuna and Eureka. It is part of the Cascadia subduction zone that threatens Oregon and Washington. There is good evidence that a magnitude 9 earthquake took place along the system in 1700, and there is no reason to think that the fault system is any less dangerous now.

|

| An offset curb on the Calaveras fault in Hollister, CA. It isn't the San Andreas... |

Question #4

: In an earthquake, the ground opens up and swallows people: true or false?

True, but only in Hollywood....

Indeed, it is a staple that if an earthquake happens in a movie, somebody is going to be hanging by their fingernails on the edge of a vast deep chasm that has opened up beneath their feet. In the third Indiana Jones movie, for instance, and in

2012, again in

San Andreas, and again, and again. And again.

For the reality-based world, the possibility of being swallowed up in the earth during an earthquake is far more unlikely. The problem is that earthquakes are generated by the stress built up along fault lines where vast blocks of rocky crust are in contact. The shaking begins when the rocks rupture and begin slipping. They don't separate. In some faults (thrusts) the stress is compressional and in others (strike-slip) the stress is lateral. Not much chance of openings occurring in either situation. The third type of fault, termed normal faulting, the stress is extensional, which could conceivably result in the stretching of the crust and formation of fissures, but more often, one side slips downward, as can be seen in the picture below, from the 1954 Fairview Peak earthquake in Nevada.

It is true that small fissures will open along fault ruptures in some situations. I saw many of these when I visited the Landers area a week after the 7.3 magnitude earthquake in 1992. The fissures were only a few inches across and no more than a foot or so in depth. I've heard mention of where someone was killed in a fissure that opened up in a 1948 quake in Japan, but that hardly represents a pattern.

One other effect of large earthquakes is the production of slope failures and landslides, during which large fissures might open up. The Turnagain Heights liquefaction event during the Alaska earthquake of 1964 is a stunning example. Weak saturated sediments underneath the housing project were severely shaken, causing the whole landscape to break up and flow towards the adjacent bay, destroying the dwellings at the surface (I've included two pictures derived from my old slide collection, but I'm afraid I don't know who to attribute them to; I will add credit if someone can clue me in. They may be from a USGS collection).

In the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, there were not any claims of swallowed people that I know of, but there is the famous tail/tale of Shafter's cow, which was swallowed up by the San Andreas fault. In the aftermath, only the poor bovine's tail could be seen at the surface. The story apparently became widespread, but in a letter from 1966, some locals recalled that the poor cow had actually died the night before. The earthquake produced a convenient fissure, the farmer tossed in the carcass, and when reporters showed up asking questions about the poor animal, farmer Shafter decided not to kill a "good story".

Question 5:

Psychics predict earthquakes: true or false?

|

| Comic art by Zeo (with slight modifications by Geotripper) |

Well, let's see if I can't make a few (seismic) waves here.

My audiences and readers are skeptics and non-believers, to be frank, and usually come down firmly in favor of "false" for an answer. So they are a little surprised when I tell them the actual answer:

TRUE!

Think about it a moment, and you will realize that the statement is in fact true. Psychics predict earthquakes all the time. All the time, and then some more. Earthquakes are one of their most common predictions, more popular I think than predictions about aliens.

That leads to a revised question: Do psychic predictions about earthquakes come true?

My readers are usually onto me by now, and they will say that psychic predictions are invariably wrong. I set them straight. I say "Psychics predict earthquakes all the time, and are almost invariably correct".

I support my contention with a collection of predictions that I googled in about five minutes. I refuse to link to each of them because I have no interest in promoting their websites. If you want to find them, google the statement and it shouldn't take long to dig them up.

- Both earthquake and out of control fires will effect California causing devastation and loss [of] life.

- There will be a violent earthquake, one of the strongest on record.[no location noted]

- My California earthquake prediction: yes, there WILL be an earthquake in California. I am not saying it will be along the San Andreas Fault or that it will be major. …I am also not saying when.

- I keep seeing the year 2011 like a pulsating animation within visions of major earth shifts in my home state of California. Dates perceived in months or years could be argued to have limited value in forecasting a time because we psychics move our consciousness in large spans of time and cover broad areas of locations and events.

Note how every one of these predictions came true. Oh, and my favorite, the shotgun prediction....

Wild Weather Predictions

- Category five hurricane wipes out Miami.

- The worst mudslides in California’s history will occur.

- Mount St. Helens erupting.

- Earthquake Seattle, Washington.

- Earthquake Chicago, Illinois.

- Part of the polar ice cap melts.

- Wildfires spread to Beverley Hills and Los Angeles, Brentwood.

- More tsunamis Sumatra Indonesia, Alaska, Hawaii and Japan.

- A great earthquake in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego.

- Earthquake Lake Tahoe.

- Earthquake Toronto and Quebec.

- Earthquake Oregon.

- Earthquake Grand Canyon.

- Earthquake New York, Alaska, Japan, Greece.

- Earthquake British Columbia, China and Iran.

- Tornado in California.

- Floods Amsterdam, Holland, Rhine River, Germany, Bangladesh, Great Britain. Venice, Italy, Gulf Coast of Florida and France.

- Tsunami Malibu, California.

- Wildfires Greece, Australia, Texas, Hawaii.

- Mudslides in India, California.

- Typhoon in Taiwan.

- Tornadoes Oklahoma, Indiana, Texas, Illinois, Tennessee.

- Great earthquake Rome and Naples, Italy.

- Huge snowstorm and blizzards up the eastern seaboard affecting the great lakes – Toronto, Chicago, New York, Boston, etc.

- Earthquake Yosemite and Yellowstone Park.

Note how many of these predictions haven't happened yet. Still, many will absolutely take place, allowing the psychic responsible for this list to claim broad success in his or her psychic powers.

Soooo...psychics accurately predict earthquakes. Well, guess what? I can predict earthquakes too! And I can be more specific than the average psychic. Here goes..

I predict that within the next week:

- 200 earthquakes will occur in California,

- Of these, there will be a magnitude 4 quake in southern California, most likely in the Colorado Desert near Salton Sea.

- There will be a magnitude 3 earthquake in northern California, most likely north of the Bay Area, somewhere around Clear Lake.

- There will be a larger quake at the Vanuatu Islands in the Pacific Ocean, quite possibly in the magnitude 6 range.

- There will be a magnitude 5 earthquake offshore of Japan.

I think I am going to be right. You are welcome to keep count and when the quakes happen you can hail me as a psychic earthquake predictor.

You can do that, but please note that my predictions have something in common with psychic predictions: the predictions are totally and absolutely useless to anybody. They are about as useful as predicting that the sun will rise in the east tomorrow. Why? Because like the sun rising, earthquakes happen all the time, and they tend to happen in the same general places, mainly along tectonic plate boundaries (along with a few near hot spots like Hawaii or Yellowstone). It sounds impressive that 200 earthquakes will happen over the next week in California, but that happens nearly every week.

Earthquake prediction is a serious business. On the one hand, a timely prediction can save lives. But a prediction made by a credible source that doesn't come to pass is a real problem. Like the boy who called "wolf" once too often, later predictions would be ignored. Charlatans who make spurious predictions can cause panic and unnecessary stress in an uninformed population (such a prediction in 1990 caused the population of St. Louis and surrounding region to close down businesses and leave town, and also caused a media circus).

An earthquake prediction, in order to save lives, must have three elements:

- the time (within a few days at most)

- the location (specific)

- the magnitude and depth

No psychic ever provides such information, which proves the useless nature of their "predictions". No one is in a position to predict earthquakes with such precision, including seismologists. Anyone who claims some special power of prediction is lying or deluded. No one has ever once saved lives with such predictions (the one successful prediction, ever, of a quake that saved lives, in China in 1975, was based on tangible evidence, and no psychic powers were claimed or invoked).

Psychics: give up the earthquakes. Stick to the lives of the Hollywood stars. They're more predictable anyway.

Question 5 B:

Animals predict earthquakes...true or false?

My answer to this one?

??? Who knows???

The problem is perceived cause and effect. Many people who experience strong earthquakes recall strange behavior by their animals, and link that behavior to the quake. The problem is that animals may behave strangely in many circumstances that are not followed by a strong earthquake, but the behavior is not noticed or remarked.

|

| This animal is clearly predicting an earthquake. Or is about to attack. |

The other problem is how to quantify strange acts by animals. What specific animal behaviour constitutes a prediction of an earthquake? At what point do authorities declare that animals have predicted a quake?

There are many anecdotal stories about unusual activity by animals going back hundreds of years, so I for one cannot completely dismiss the idea out of hand. Animals sense the world differently than humans, and there could in fact be some sort of electromagnetic or vibrational effect that researchers have not yet detected.

A reasonable response on earthquakes and animal behavior would be a good article by the

National Geographic that can be found here. Geologists around the world

followed a story coming out of Italy regarding the failure of seismologists for failing to predict or warn the local populace before a deadly earthquake in Italy that killed several hundred people in 2009. It's one thing to say geologists can't predict earthquakes, and quite another to say they didn't predict it enough in the aftermath. Seismologists walk a fine line.

Speaking of kitties and strange behavior, if you see these eyes, run for your life. Aliens have taken over your cat's soul....

|

| Comic art by Zeo |

Question 6:

In California, we are waiting for the BIG ONE! True or False??

When I talk to groups about this question, I make sure to say "the BIG ONE" in capital letters. How do you say something in capital letters? You do it in a deep baritone voice with your hand cupping the microphone; it's very dramatic.

So what is the answer? Well, actually the question is wrong and requires a bit of modification. Let's try it again, and in that deep baritone voice:

In California, we are waiting for the BIG ONES!

There, that's better. If we can't predict earthquakes, then how can this statement be possible? Doesn't it require the ability to predict earthquakes? Yes, it does. So the statement must be false. But it is not. The answer is

TRUE!

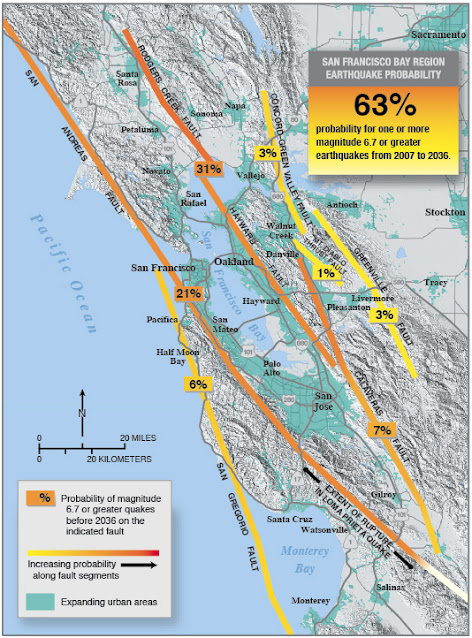

Predicting earthquakes is not possible in the short term, as in hours or days, but a great deal can be said about the probability of earthquakes in a particular area over a period of decades. We can do this on the basis of the historical and prehistorical record of earthquakes along a particular fault zone, and by analysis of building stresses and tilting over a large region, as revealed by GPS stations and other related technology Check out the latest version of the Working Group on California Earthquake Probabilities

in this USGS PDF file.

As can be found on the map above, numerous fault zones represent a threat to the state of California. The fault zones are of different lengths, and therefore some will produce smaller quakes, but several are capable of producing large shocks approaching magnitude 7, and maybe even larger. These include the San Jacinto fault, the Owens Valley fault, the Hayward and Calaveras faults, and others. Even more important is the fact that the San Andreas itself is not a single monolithic fault zone. It has segments that behave independently. This was shown in 1857 and 1906, when completely different sections of the fault gave way, producing shocks that approached magnitude 8.

The

most recently published studies show that earthquakes of 6.7 magnitude or greater are a virtual certainty over the next 30 years. The chance for an even greater quake is ominous, exceeding 70% for a magnitude 7.0, and a lesser, but still significant chance of even larger events. One of these quakes has already occurred, the

Ridgecrest Earthquake of 2019 (7.1).

Another wild card is the possibility of a large quake along the Cascadia subduction zone in the northernmost part of the state. It was not included in the probabilities, but numerous magnitude 7 quakes have taken place in that region in recent decades.

The lesson to be drawn from these predictions is that damaging earthquakes have happened all over California, and they will continue to do so in the future. Some of these quakes will be major events, causing many deaths and massive damage over large areas. The probability forecasts have great value in the sense that they are a warning to residents across the the state to be prepared at all times for earthquakes. We cannot know the precise moment that a large earthquake will strike, but we do know where they will happen, and how big they can be.