|

| Looking upstream on the Kicking Horse River at Field, B.C. |

I've called this narrative of our journey "Northern Convergence" because of the presence of a convergent plate boundary for the last 200 million years or so that has drastically altered and changed the continental margin of Canada and the Pacific Northwest. We had spent the previous four days traversing landscapes composed of exotic terranes, tracts of crust that originated someplace else and had been appended to the edge of the continent by way of subduction. The bits of crust were dragged into the trench, but were too buoyant to sink into the underlying mantle, so they mashed into continent instead, and intense deformation resulted. And the continent got bigger...lots bigger.

|

| Looking downstream on the Kicking Horse River at Field, B.C. |

The scenery was on a truly grand scale. Yoho is contiguous with Banff National Park, and yet is rarely mentioned in the same breath (it's always "Banff and Jasper", maybe because they're on the Alberta side, and Alberta knows P.R.). Yet the park is spectacular, and even better, holds a treasure of worldwide significance.

The park protects mainly the upper watershed of the Kicking Horse River which includes several major icefields, including the Waputik and Wapta. The glaciers coming off the icefields contain finely ground silt and clay that stay suspended in the turbulent water. The rivers look like flowing milk at times.

Another road reaches up into the Yoho River drainage, providing access to Takakkaw Falls, the third highest in Canada at 254 meters (833 feet). The waterfall is a textbook example of a hanging valley, resulting when the main trunk glacier carved a deeper valley than the tributary glacier. The glacier feeding Takakkaw Falls is only a kilometer or so upstream of the brink.

If you need a sense of scale regarding 254 meters, look at the picture above where the water leaps outward from the cliff near the top of the waterfall. Let's zoom in on it. Those little dots to the left? Rock climbers!

There is a problem with understanding the ecosystems that existed millions of years ago. Usually only the shells and bones are found, but the vast majority of organisms had soft bodies that are rarely preserved as fossils. They would invariably decay quickly. Fossil localities with the remains of soft-bodied organisms are few and precious, and our students were investigating one of the world's most famous. The Burgess Shale preserves the fossils of soft-bodied organisms that were present only a few million years after the dawn of complex multi-celled lifeforms.

How did they come to be preserved here? Just over 500 million years ago, the region was at the edge of the continent in relatively shallow water at the edge of the continental shelf. The shelf was unstable and occasionally a mass of mud would break off and sink into deeper water, carrying with it the organisms that were living there. The blocks sank into oxygen-starved water where the bacteria that would have consumed the soft body tissue could not survive. Mud covered and preserved the dead organisms. More than a hundred species have been described here.

The fossil quarry lies high on a ridge above Emerald Lake between Field and Wapta peaks. You can pick it out in the picture below, as the horizontal gash in the hillside with the lowest patch of snow. The hike is not easy, really an all-day affair. The quarry is a World Heritage Site and access is strongly restricted, and obviously collecting is not allowed. I've heard they've even gone after fossil sellers active on E-Bay.

I did the hike in 2005, so I didn't try it this time, opting instead to let my fellow professor hike with the students (she might forgive me the blisters one of these days...). The hike was one of the great adventures of my life, though, and I described it in detail in a post last April: you can read it by clicking here. There just aren't many times in life when you can be so close to the ancient past.

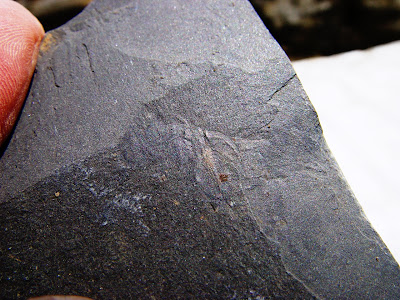

|

| Holding a specimen of Marrella splendens in the Burgess Shale quarry, 2005 |

We visited with the local wildlife, and then headed over Kicking Horse Pass into Banff National Park. More adventures lay ahead!

|

| A Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) at Field, B.C. |

I hope that somebody appreciates that I made it through an entire post about a place named "Yoho" with nary a single "Pirates of the Caribbean" joke.