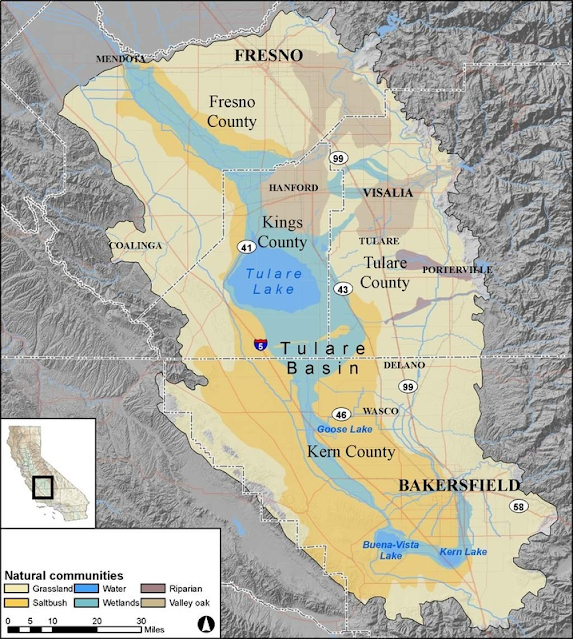

The Great Valley of California is a great place to see a lot of birds in one place. In pre-colonist days, the 400-mile-long valley was a prairie that was watered by a series of rivers flowing from the adjacent Sierra Nevada. There was enough water that even in historical time there were two immense lakes between Bakersfield and Fresno, Tulare Lake and Buena Vista Lake. Before water diversions for irrigation caused it to dry up, Tulare Lake was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi.

|

| Source: Quora |

|

| The ecological role of grazer in the refuges is occupied by a handful of deer and lots of sheep and cows to make up for the now-extinct megafauna |

But historical accounts and paleontology can provide us some idea. In addition to birds, the vast prairies supported huge herds of tule elk, deer, antelope, and even bison. Prior to 12,000 years ago, the plant-consuming animals included giant ground sloths, mammoths, mastodons, horses, and camels. The birds and grazing animals were the prey of an imposing array of predators including the recently departed California Grizzly Bear, black bears, wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, and foxes. The pre-12,000-year crew included saber-toothed cats, dire wolves (bigger than wolves of today), American Lions, jaguars, and the immense Short-faced Bear, an animal that would have made a Grizzly think twice about a confrontation. The reason for the almost simultaneous extinctions of the species of the so-called 'mega-fauna' is a subject of contention among geologists, paleontologists and anthropologists (the role of humans has not been ruled out).

|

| This cuddly little Short-faced Bear can be seen at the Fossil Discovery Center near Madera |

The national wildlife refuge system grew out of a number of motives, some noble, others not so much. When wetlands of the valley were drained and planted with crops, millions of birds found their ancestral winter homes gone. With nowhere else to go, many of the geese and others began to forage on the tilled fields to the distress of the farmers. Instead of massacring untold numbers of birds, a series of refuges were established up and down the valley to provide a haven and food for at least some of the migrants. Of course, the refuges were also designed to preserve populations of the birds so they could be shot. Much of the refuge funding comes from the sales of hunting permits.

|

| Snow Geese at the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge |

So that is where are today. The refuges provide forage for millions of migratory cranes, geese, swans and ducks (in many they grow fields of corn for the singular purpose of feeding the birds). The birds are too crowded, and diseases can spread if the flocks are not managed properly, but it is a better situation than having no refuges at all. Some species, especially the Aleutian Cackling Goose, have been brought back from the brink of extinction (once down to just 300 or so birds, the population is more than 100,000; they mostly shelter at the San Joaquin NWR just west of Modesto). And yearly, more and more abandoned farmlands are being converted to the original riparian habitat to allow for population growth.

I don't do video often, but the one at the top seemed necessary because I was looking at what I believed was the largest single grouping of birds I've ever seen (and I've been exploring these refuges for 7-8 years now). It required about a 180-degree pan. On the other hand, there is nothing in the world quite like watching thousands of geese taking flight all at once. When we were at the San Luis NWR last week, the serene view was of several thousand Snow Geese and Tundra Swans. It's not really a good thing for the birds to be scared into the air, as it uses precious energy, and they could get hurt. But a helicopter flew overhead at a low elevation, and it spooked the geese (the swans seemed like they could care less) and several thousand took flight. I caught the flight on video, and you can clearly hear the helicopter. I took a picture of the craft thinking to report it, but it turned out to be medi-flight out on an emergency call.

This Great Egret was at the San Luis NWR. Both refuges offer "auto-tours" where visitors stay in their cars (kind of like those African savannah tours, but there aren't any lions trying to eat you). The cars serve as blinds, startling birds far less than humans bumbling around.

We were looking for swans and saw large white birds off in the distance. They turned out to be American White Pelicans. They may be the most ungainly-looking birds on the ground but are positively graceful in flight. And they are huge.

We were looking for swans and saw large white birds off in the distance. They turned out to be American White Pelicans. They may be the most ungainly-looking birds on the ground but are positively graceful in flight. And they are huge.

The prize for wildest beak goes to the Long-billed Curlew. I guess they can reach bugs and worms in the mud and soil that other birds can only dream of.

The Greater White-fronted Goose may be one of the more unfamiliar goose species around the valley. I've seen only a few in urban settings. Like the others, they are long-range migrants.

The Greater White-fronted Goose may be one of the more unfamiliar goose species around the valley. I've seen only a few in urban settings. Like the others, they are long-range migrants.

One of the special treats for the last two or three years has been a female Vermilion Flycatcher that decided to spend winters at the Merced NWR. This is the extreme north end of their range, and only a few are ever seen on a yearly basis in Stanislaus or Merced counties. Global warming may be allowing them to expand northward, and it may be only a matter of time before the scattered males and females find each other and start making little flycatchers.

This is an American Avocet, another bird that has a crazy bill that is good for probing deep in the mud.

There are a goodly number of raptor species that live in the refuges. One of the most beautiful is the White-tailed Kite. We thought we were done with photo opportunities when we reached the open grasslands at the end of the auto-tour at Merced, but this kite was perched on the sole tree eyeing the ground squirrels (and they were eyeing it).

The last bird of the day was the biggest surprise of all because it was the first time I had seen it in several years. It's a Black-bellied Plover, and it's not all that rare. It's just that I don't always know to look for it or recognize it when I see it. And it doesn't have a black belly. The males grow it when breeding season comes along.

This is an American Avocet, another bird that has a crazy bill that is good for probing deep in the mud.

There are a goodly number of raptor species that live in the refuges. One of the most beautiful is the White-tailed Kite. We thought we were done with photo opportunities when we reached the open grasslands at the end of the auto-tour at Merced, but this kite was perched on the sole tree eyeing the ground squirrels (and they were eyeing it).

The last bird of the day was the biggest surprise of all because it was the first time I had seen it in several years. It's a Black-bellied Plover, and it's not all that rare. It's just that I don't always know to look for it or recognize it when I see it. And it doesn't have a black belly. The males grow it when breeding season comes along.

|

| Sunset at the Merced NWR |

Better get out there soon, folks. The bird numbers are dropping. If you go on midweek afternoons, you'll have the place to yourself!

ReplyDelete