"The region

. . . is, of course, altogether valueless. It can be approached only from the

south, and after entering it, there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been

the first and the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It

seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of

its lonely and majestic way, shall be unvisited and undisturbed."

Joseph

Ives (1851)

Joseph Ives did a lot of hard and dangerous work to be remembered only for the famous quote shown above. His expedition spent months exploring the region, collecting huge amounts of data on the geology, hydrology and biology. Often cited as one of the most incorrect predictions ever uttered, the statement to a certain extent is actually true. Nearly five million people do in fact visit Grand Canyon National Park every year, but the vast majority of them merely stand on the rim and look down. Tens of thousands may hike down the handful of popular trails, and a few thousand float down the Colorado River. But hundreds of square miles of the park see no visitors at all most years. The canyon is mostly inaccessible, and I have no doubt that there are many new discoveries to be made about the geology and biology.

Profitless? Pretty much true. A handful of mines in the Grand Canyon made modest profits, but most mining ventures failed, due to poor ore values and lack of access.There is no lumber to speak of within the canyon, and utilizing the water of the Colorado River was impossible until the great dams of the twentieth century, and they aren't actually in the Grand Canyon. Tourism is the only economic gold mine around here.

It is possible to look at the canyon and not be impressed. When Coronado's troops reached the rim in 1540, their perspective was so skewed that they thought the mile-deep canyon was only a thousand feet deep and that the Colorado River was only six feet across. A day spent trying to scramble down the cliffs quickly cleared the misconception, and they left the region. For literally centuries.

I think the same sort of thing happens with casual tourists, too. It is so easy sometimes to step out of an RV where one has been watching a large screen tv and see the vast depth of the canyon as a flat canvas, very colorful, but without depth. It's so easy to snap a few pictures and head on to the next overlook or the next park. As has been said so many times, the only way to really appreciate the scale of the Grand Canyon is to see it from the inside out, to walk it, to ride a burro into the depths, or to float on a raft down the Colorado River.

I have no doubt that someone also thought of the other alternative: build paved roads and let people wear out their brakes on a drive down to the bottom and look back up before destroying their transmissions and radiators on the steep climb back out. There are just one or two problems with that: besides invading the precious wilderness that lies below the rim, there is the Coconino Sandstone, and the Redwall Limestone. There are engineering problems with practically all the Paleozoic and Proterozoic formations of the canyon, but these two are especially troublesome. They are cliffs of such uniformity throughout the Grand Canyon that there are only a few dozen places where trails can breach the inner canyon. Roads? It just can't be done (or else it would have done in the formative years of the National Park Service; think of Going to the Sun Highway at Glacier, Tioga Pass in Yosemite, or the Crater Lake Rim Highway). If you have only that precious few days of vacation, you are going to want to see as much as you can of all the parks in the region, and leave the four day backpack to that unspecified future time when you get back into shape...

|

| Yeah, they got the trail through the Redwall Limestone here; but where would you put a highway? |

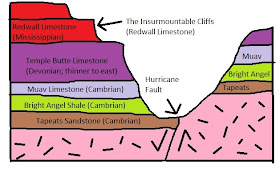

So that was my conundrum last month. How could I share the incredible story of the Grand Canyon with my students when there were 34 of us, and only a day? It turns out that there was one place where I could drive them down the canyon: Peach Springs Road and Diamond Creek on the Hualapai Reservation in western Grand Canyon. It's a winding 21 mile road that reaches the Colorado River 4,000 feet down in the gorge. But how could they have constructed this road? I don't know when it was built or why (anyone out there have some info?), but they did it. It was all the fault of...well...the fault. The Hurricane fault to be specific. The fault has dropped the rocks on the west side over a thousand feet, so a route could be selected that simply never had to cross the cliffs of the Coconino or Redwall (see the diagram below). The road starts in the Devonian Temple Butte Limestone, and only has to drop through the Cambrian sediments and the underlying complex of Proterozoic gneiss and granite, which is rugged enough, but the erosion of Diamond Creek did most of the work before the roadbuilders arrived.

The road is utilized as a major take-out point on the Colorado River by the rafters. It is not a particularly good choice for the casual tourist. It's not so much that it is too rugged, but in summer the temperatures are sizzling, and this exacts a toll on radiator and electrical systems. You may remember reading about my own failure to reach the Colorado River a month earlier due to car problems. It's also expensive; the Hualapai nation charges $25 per person to drive the canyon (I didn't mind paying; tourism is pretty much the sole income for the tribe). But we did it with students this year for the first time ever. That story comes in the next post.

Here is the explanation of my "abandonment" theme for this series: http://geotripper.blogspot.com/2012/06/abandoned-landsa-journey-through.html

I don't know it is encouraging or discouraging to hear, but there are places on the planet where we can, and do, take very small groups of students for field-trip based classes. Our university, in northern Sweden, has been sending undergraduate students to Cyprus each spring to see the opholites and many other geologic points of interest. This year was the largest group yet--nine students, one professor, and a post-doc (me), and PhD student as supervisors for the trip. We did our tour using three different rental cars, and it was hard to keep together. In past years they could get away with only two cars. We are wondering what will happen next year, since we had a record 27 students sign up for the program, and taking that many to Cyprus will be a logistical nightmare...

ReplyDeleteI really should make time to turn my photos of the trip into a blog post...

(Note: University education in Sweden is free--the students paid only for their own food on this trip (we stopped at a grocery store daily for people to buy stuff for lunch to take with us in the field)--the flights, hotel room, and rental cars were all provided.

@A Life Long Scholar:

ReplyDeleteI just went to Cyprus on a field school (with the University of Victoria, in British Columbia, Canada). There were 23 students and 4 instructors, we rented three 9-passenger minivans, and stayed in Larnaca as our 'home base' for 10 days. It was amazing, and while we had to pay for our flights there and our food, the rental cars and hotel was paid by the university.

While it was not cheap, it was totally worth it. It was fairly easy for us to stick together in the vans, as they were pretty big vehicles for Cyprus and easy to spot on the road. We stayed 4 people per room in the hotel (they had kitchens in the hotel room too!) which helped cut costs as we could make our own dinner and lunch.

I came out the Diamond Creek road after last year's river trip and although very rough found it an amazing experience. Just wish we could have stopped for closer looks along the way.

ReplyDelete